This is an introductory survey of a vexed issue of book-production: binding techniques. The intention of the piece is general enlightenment, and to support a process that is threatened with extinction. A version of this article was published here in May 2007. The text and images here are a new version of this article – thoroughly revised and reshaped in April 2018.

Aims and ideals

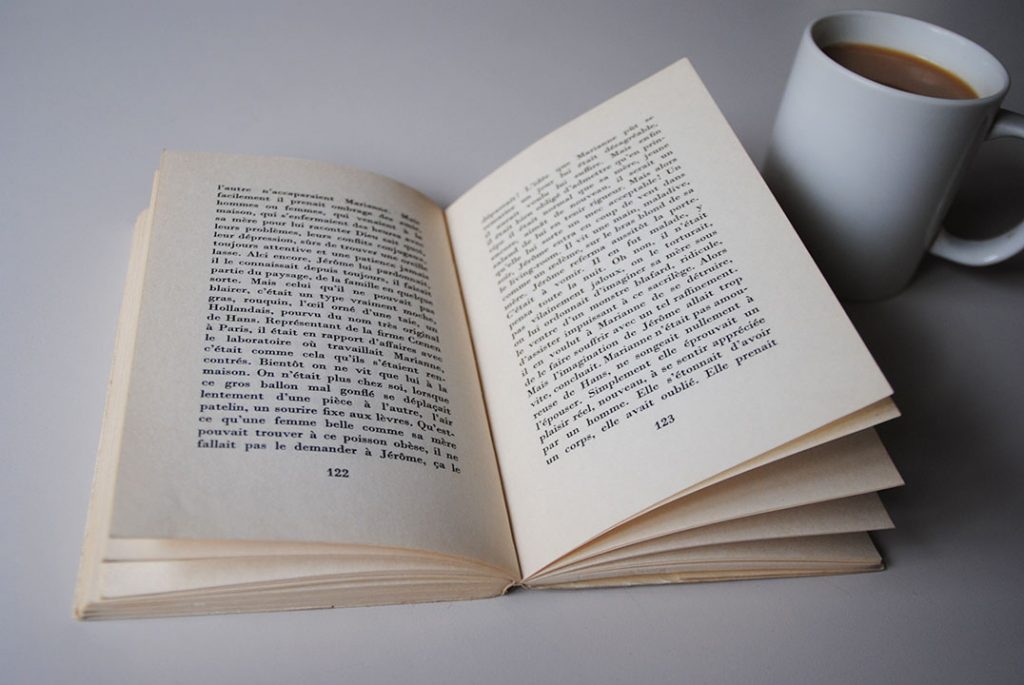

A book, when opened, should lie flat when placed on a table, and stay that way without help from its reader’s hands. It should open to its fullest extent, so that the whole of the page, or pair of pages, can be used: for photographs that might run into or across the central margins, for side-notes or other text that needs to occupy an inner margin. One might remark also that a book open on a table – while the reader holds a cup of tea in both hands (for warmth and comfort), or sews a button on a shirt, or carries a young child – is no more than a mark of decent civilization. So the binding should be strong enough to withstand this opening-out. The spine will of course begin to show signs of wear with this opening – that is in the nature of the materials – but it should not split, and the pages should not fall out.

The book-block

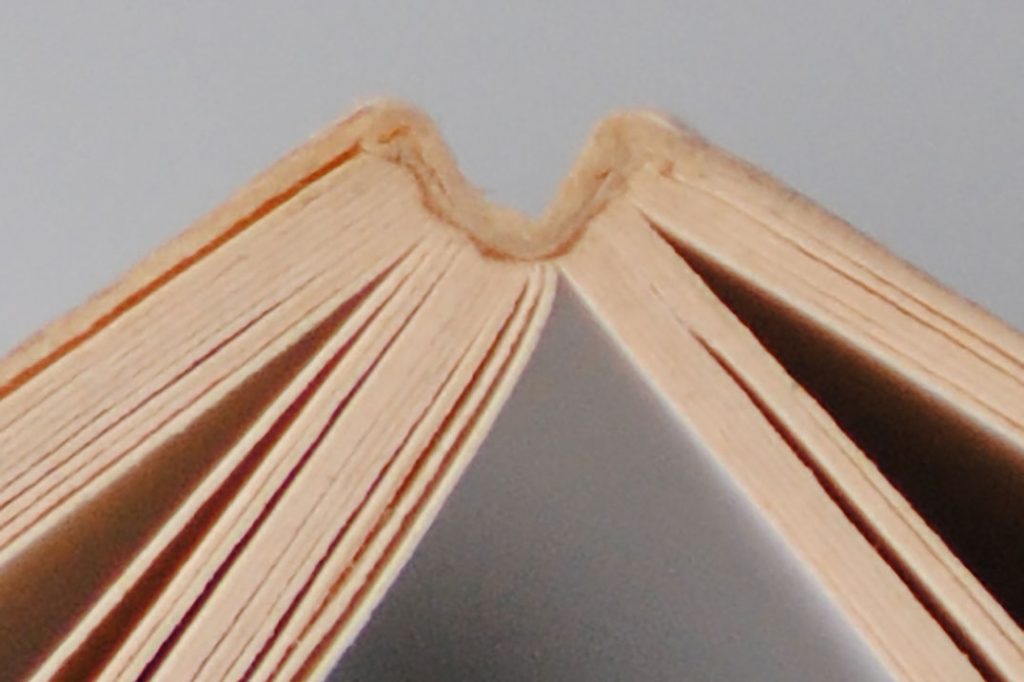

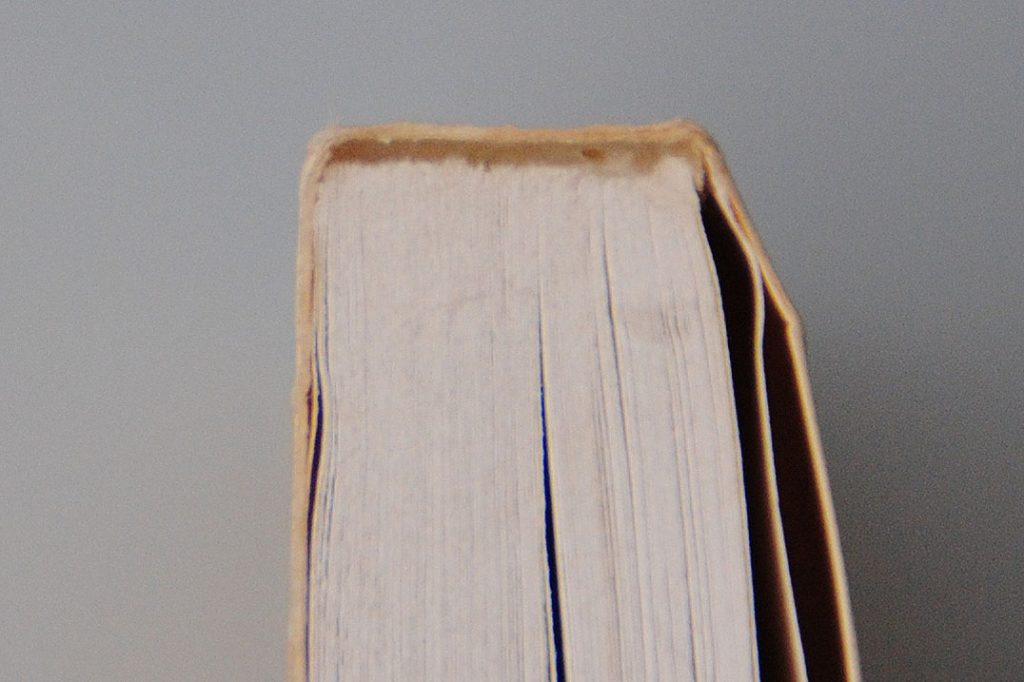

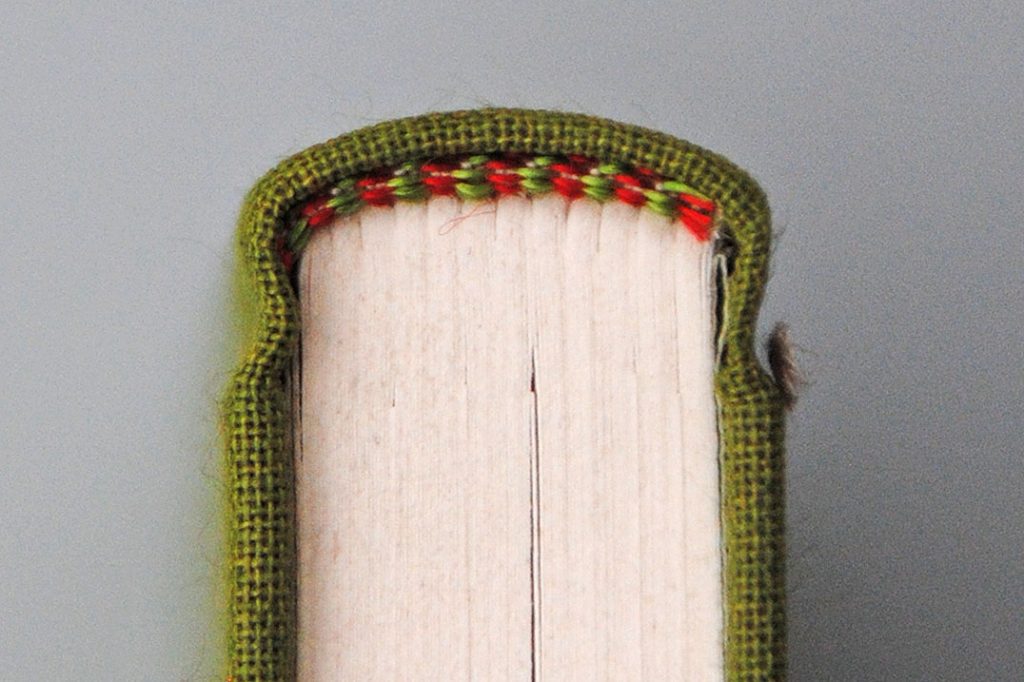

Printed sheets are folded to make sections, which are gathered together, and then secured to make the book-block. Easy opening follows from how well the sections are secured. If they are sewn and principally held together by threads, this should work well (and it allows the book to be easily rebound years later, if the covers have become worn out). This old method now comes with significant monetary cost, and a bindery may have disposed of the machines that could do it. More usually now, the means of holding pages together is an adhesive. The backs of the sections are cut and then the adhesive is applied, or a layer of adhesive is applied to the sewn sections, or some mixed process is used (for example in ‘burst’ binding) in which the sections are residually evident.

Paper

Paper is materially biased. Any paper – even the blandest, most thoroughly industrialized material – has a grain. This is the direction in which its fibres point. A sheet of paper will want to bend along and not across the grain. The grain may not be visible, but can be discovered when the paper is moistened or when kept in damp conditions. (There are a number of simple tests one can make to determine grain direction: the simplest being to bend a sheet horizontally and then vertically, and see which one offers less resistance.) A book that might seem unproblematic in its performance, when first viewed, can change in its material behaviour when you travel with it through differing atmospheric conditions. So the grain should run parallel to the spine of the book. If the grain runs at right angles to the spine, the pages will tend to curl in ways that impede opening out.

Printers should not need to be asked to ensure correct grain direction (it might be like asking a baker to ensure that their bread is properly baked). But now, at least in the Anglo-American sphere of book production, grain direction is quite often wrong. Some reports suggest that this follows from the way in which the production line in the printing works has been designed. Then it will be hard, perhaps impossible, to produce books with the right grain direction, without discarding the installation and rebuilding it with other machines.

Adhesive

The nature of the adhesive is a fundamental factor in successful opening. Broadly, two kinds of adhesive are used in present-day book production: water-based glues and plastic materials.

Almost invisible cold glue on a paperback. (Wilhelm Busch, Max und Moritz, Zurich: Diogenes, 1974)

Glueing with water-based adhesives – known in English as ‘cold glue’ – is the older method. The material is liquid already in its cold state. With this material, the job can be done with only a very thin layer of glue – minimal thickness is itself an advantage – and these glues are flexible and durable. They take 24 hours to dry, and production will have to be halted for this. PVA (polyvinyl acetate) is another name for this category of adhesive.

A thick layer of unyielding hotmelt on a paperback. (Terry Eagleton, Against the grain, London: Verso, 1986)

Glueing with plastic materials that are heated to become fluid is often termed ‘hotmelt’ (in English and now other languages). The process goes fast, and drying is almost instant. This speed is the obvious appeal of the process. But these adhesives are less flexible than a water-based glue. The thicker the layer of adhesive on a spine, the more resistant it will be to opening. The more pages in a book, the less this may matter. But even a 400-page book, its sections held together with threads and a layer of hotmelt adhesive, will not open as well as a cold-glued book.

PUR (polyurethane reactivate) constitutes another category of adhesive. Like hotmelt materials, it comes in a solid state and is then heated before application. PUR bindings may need a thinner layer of adhesive to hold the pages, but their ‘stay open’ qualities are not better than hotmelt, and they are said to suffer from the emission of toxic vapours when heated.

Wreckage from the 1970s: a hotmelt paperback with a broken spine. (Francis D. Klingender, Art and the industrial revolution, St Albans: Paladin, 1972 [1975 reprint])

The hotmelt plastics have been improved over the years. One can find vivid examples from the 1970s (when the process became prevalent in western Europe and North America) of books whose adhesives quickly hardened and then split wherever they were firmly opened. By contrast, one can find cold-glued spines from long ago that still open, and stay open, perfectly. Their paper may now be browned and mottled, but the book-machine functions as well as it always did.

Much of book production now runs without access to cold glue. Apart from hand or ‘craft’ binders, it has disappeared from use by binders in North America, the UK, and much of continental Europe. When asked to use cold glue, a printer or binder – if they still have access to it – will say that it isn’t suitable for books that are printed on coated paper. The thin fluid may seep through the holes of the threading needles and form a pool inside a section, or between two sections, which, when dry, then pulls away a patch of the paper when the pages are opened out. This has happened since coated paper was invented and may be a problem for fetishists who live only for the perfectly smooth finish, and don’t actually use or read books.

Hardbacks and paperbacks

The book trade distinguishes severely between hardbacks and paperbacks; though the truth is that each comes in all manner of forms. A well-made paperback is preferable to a poorly constructed hardback. And in its materials and processes, such a paperback may cost more to make than the poor hardback (yet is expected to sell for less than half the price of the latter). The advantage of a hardback – apart from its thicker, harder, more durable covers – is that the book-block is held apart from the back of the cover. So the block has an easier time when it is opened out: there is no back to constrain it, or to become creased. A cold-glued, thread-sewn block inside hard covers can become a wonderfully easy mechanism.

A paperback has paper covers that are glued to the block of the book. So when the back of the block is opened, the covers have to open too. This is the moment for cold glue to do its business: hold the pages together strongly and flexibly. Over time and with use, creases will appear in the spine of the paperback. This is life – it is what happens when goods are used. Creases in a spine are a sign of a book that has been worth reading and consulting.

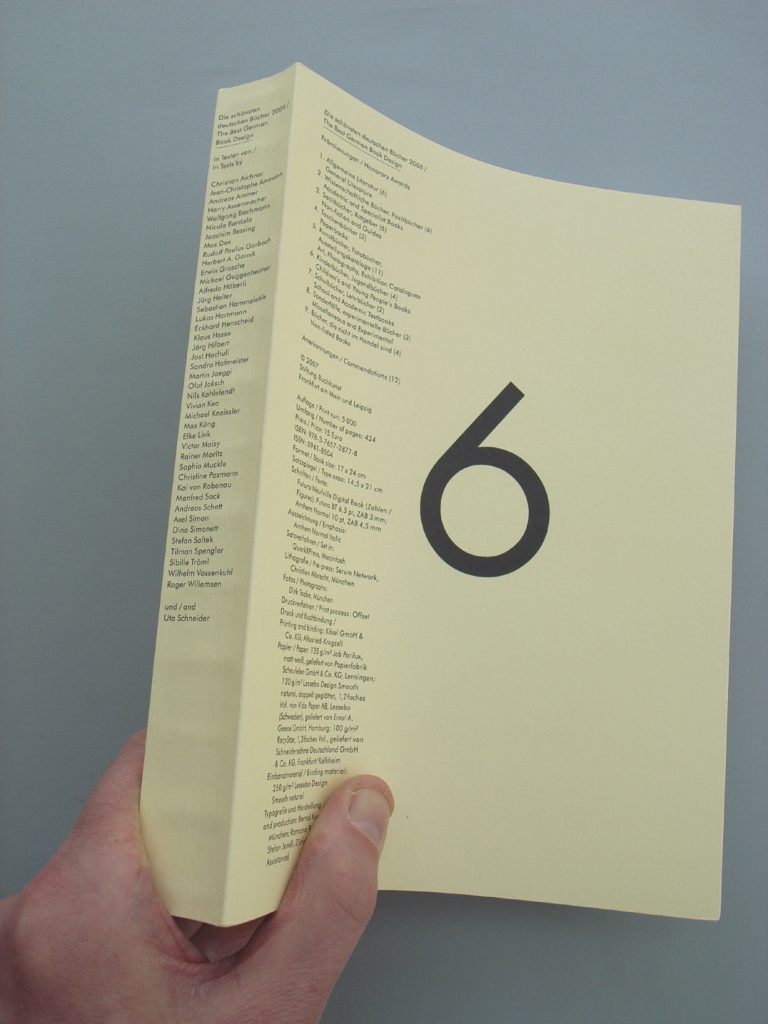

A further possible objection to cold glue arises here. In a cold-glued paperback with sewn sections, the points at which the threads are sewn together, at regular intervals down the spine, form a succession of small ridges, which can be felt as one runs a finger down the outside of the spine. Again, lovers of smoothness above everything may not like this. Others will not notice, or will even find it pleasant to feel the construction beneath the skin.

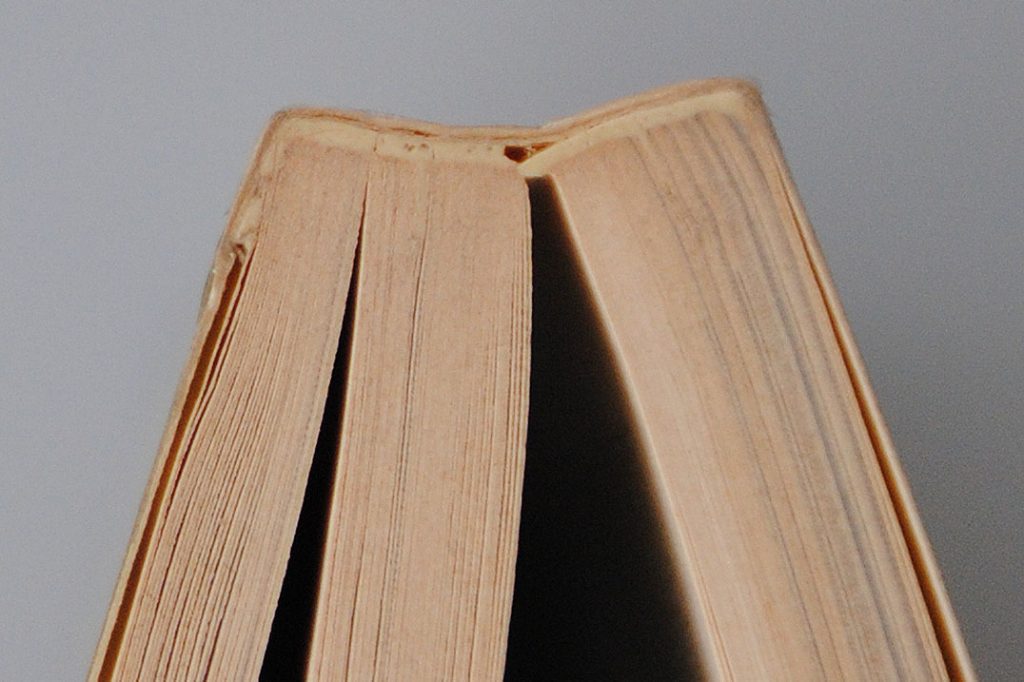

The threads below the cover can just be felt in this elegant and wonderfully strong cold-glue binding. (Die schönsten deutschen Bücher 2006, Frankfurt a.M. / Leipzig: Stiftung Buchkunst, 2007)

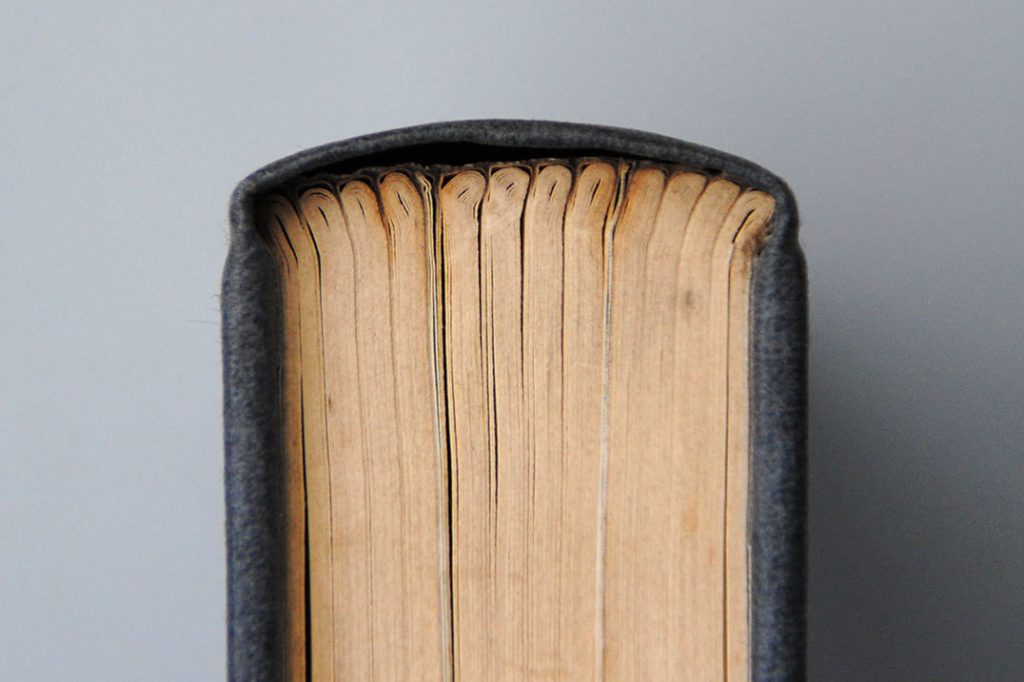

A hardbacked book will have stiff covers. But beyond that, there are many kinds and qualities of hardback. For example, a cold-glued thread-sewn hardback may be achieved by various means and with varying results.

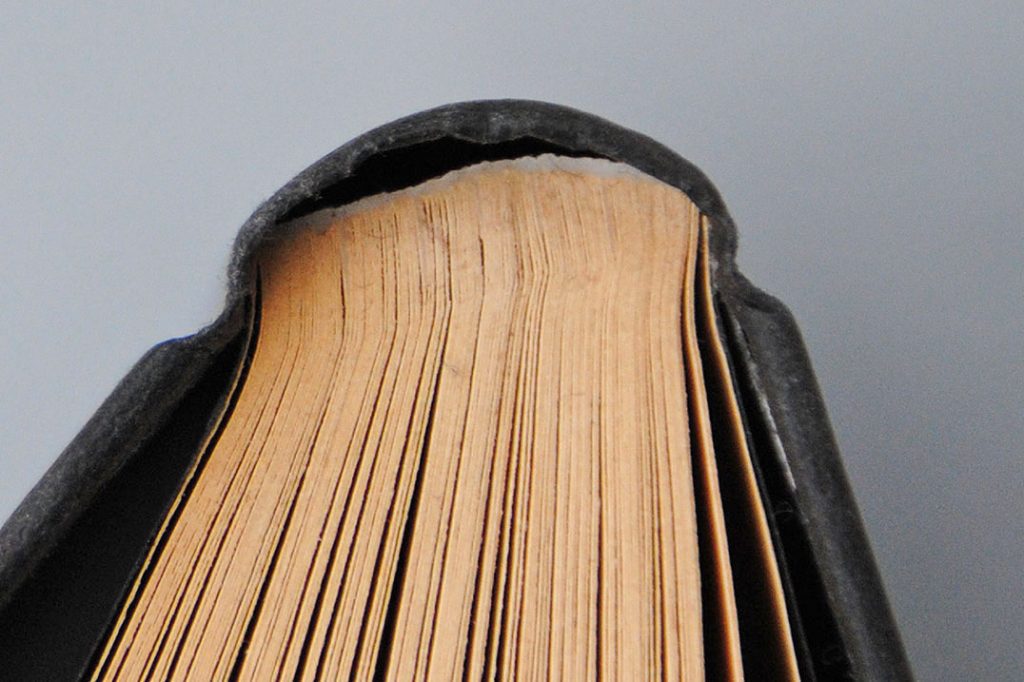

Brutally splayed sections in a cold-glued hardback binding. (Ilsa Barea, Vienna, London: Secker and Warburg, 1966)

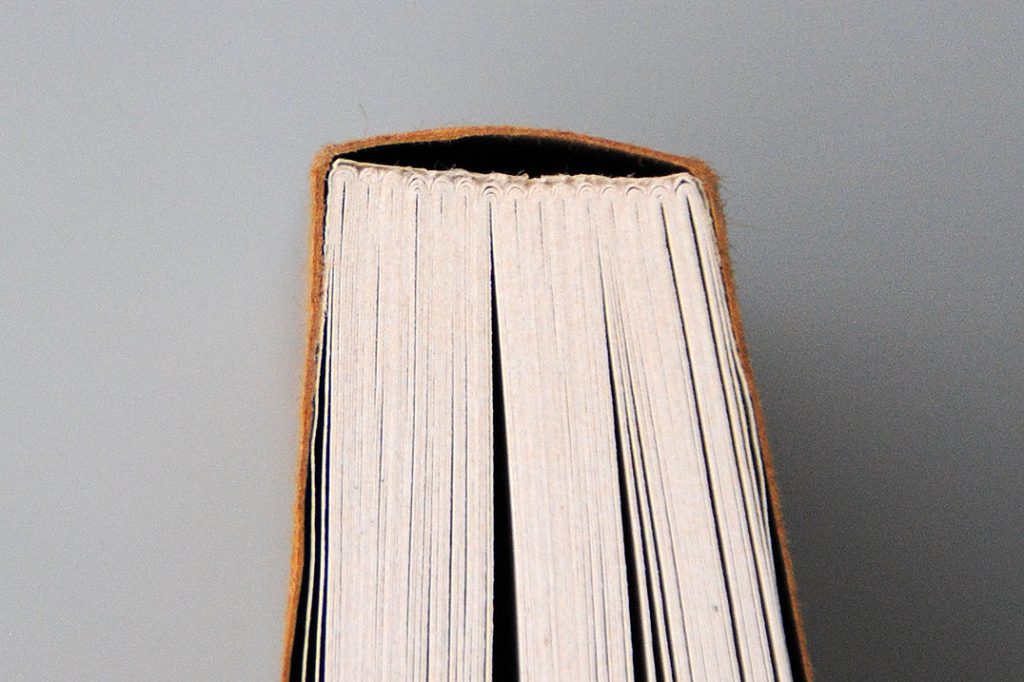

Elegant, well-rounded sections in a cold-glued hardback binding. (W.G. Sebald, Logis in einem Landhaus, Munich: Hanser, 1998)

For reasons of speed and economy, thread-sewing is now not so often used in the manufacture of hardbacks. The book may then be, in effect, a paperback clothed in hard covers. If the adhesive that keeps the cut (perfect-bound) sections together is a thick, hardening hotmelt, then the result won’t be good.

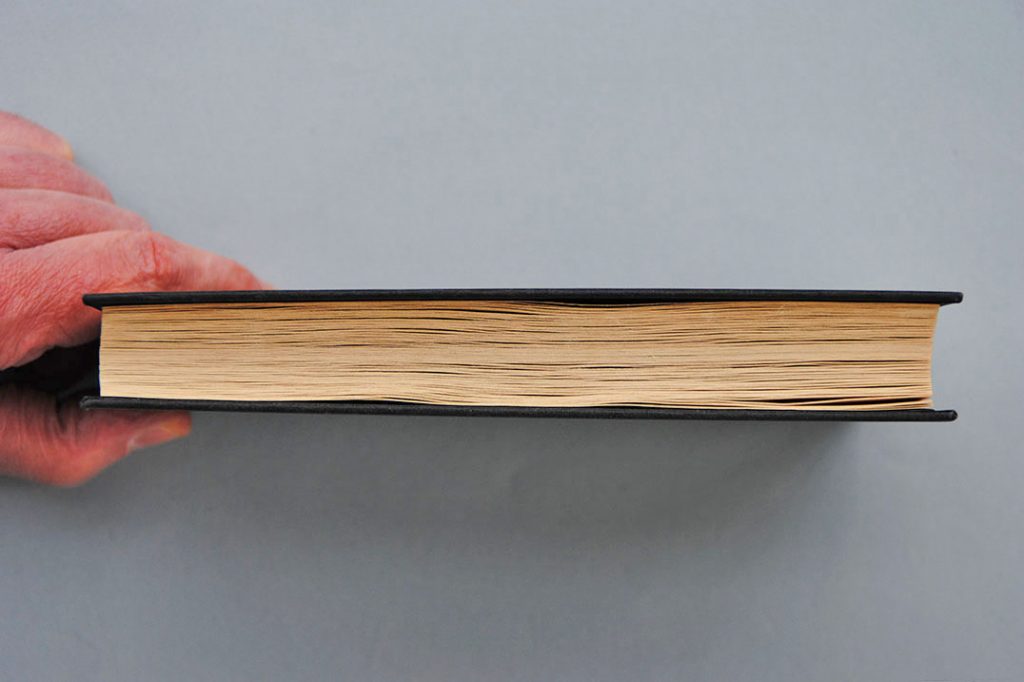

A typical hotmelt binding in a hardback, the sections cut as in a perfect binding. (Lynne Truss, Eats, shoots & leaves, London: Profile Books, 2003)

The opening properties of a book are not helped when the grain of its paper runs across the pages. (Lynne Truss, Eats, shoots & leaves, London: Profile Books, 2003)

Hybrid bindings

Binders have always developed special methods. One important idea of recent years has been the paperback whose block is held away from the cover sheet. The potential virtues of the paperback and the hardback are thus retained: a soft cover and spine that does not have to undergo the book-block’s flexing out. In Europe, one such method was invented by the Finnish company Otava, the large publishing and printing firm that dates originally from 1890, when it was founded as a vehicle to aid the emerging Finnish national spirit.

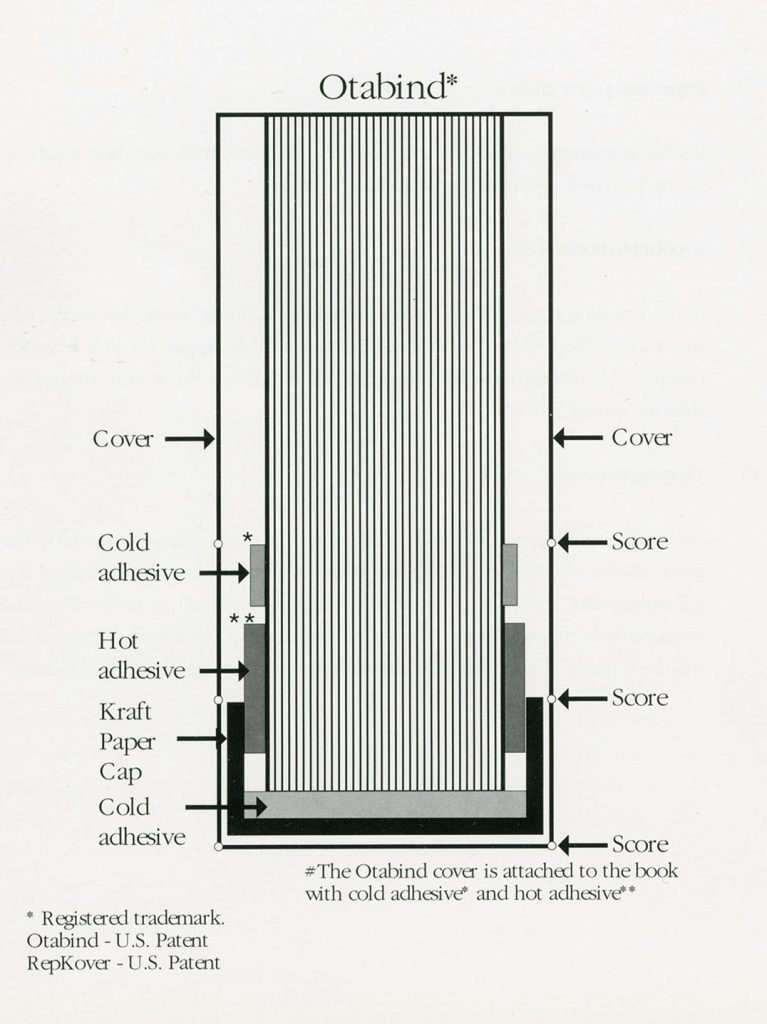

Otava came to develop its own binding method for schoolbooks, which needed to be both cheap in materials and to lie open easily on tables and desks. The book-block is fixed to a thin sheet of paper, which in turn is fixed at its sides to a cover, which is scored at least twice on each side. This technique has come to be known as Otabind.

In the 1980s Otava granted a non-monopoly license in this method to the Dutch binder Hexspoor, whose factory was situated in Boxtel in the south of the Netherlands. Hexspoor was then run by Gerard J.P.M.T. Hexspoor, who had taken over the firm from his father, who had founded the company in 1946. For a time Hexspoor named the method ‘Hextrabind’. But when it came to exploting the license overseas, Gerard Hexspoor formed a new company, Otabind International. The Otabind patent consisted in a description of the method. Müller Martini, the Swiss manufacturer of binding machines, had helped Otava develop the method and now worked together with Hexspoor in its wider application.

From a booklet published by Otabind International BV for Drupa 1995

These patents ran for only 10 to 20 years, so the Otabind method is now free for use by any binder open to designing and installing the plant needed to achieve it.

At the same time as Hexspoor was exploiting the Otabind idea, in North America a very similar method was developed, principally by Werner Rebsamen, and marketed there. This variant, which added a strip of cloth around the book-block, was given the trade name RepKover (standing for ‘reinforced paperback cover’).

Otabind is not in itself a desirable binding method. Adhesive is still the crucial factor. Otabind with the pages cold-glued (perfect-bound or sewn) will always work much better than Otabind with hotmelt. So too a cold-glued paperback (perfect-bound or sewn) has these advantages over Otabind with hotmelt.

Otabind at its best, with cold-glued sections. (Brussels: a manifesto, Rotterdam: Berlage Institute / NAi publishers, 2007)

A RepKover binding with hotmelt, adopted as a standard for its books by the publisher O’Reilly. (Chuck Musciano and Bill Kennedy, HTML and XHTML: the definitive guide, 5th edn. Sebastapol: O’Reilly, 2002)

The present situation

Outside the domain of the hand- or craft-binder, cold-glue binding has almost disappeared. Enquiries here in the UK suggest that there are no binders able to do it. This must be a matter of ignorance and economic calculus. But there are perhaps a handful of binders on the continent of Europe who can still provide cold-glue binding for paperbacks and hardbacks (see the list of binders given at the end of this piece). These are fully commercial binders, working on an industrial scale. The exception is Mathieu Geertsen, which describes itself as a ‘hand’ binder; though Geertsen too will bind an edition of thousands, as well as one of smaller numbers.

In January 2018, the Hexspoor binding business was bought by the old-established Belgian publishing and binding firm Brepols. The Hexspoor firm will continue with its warehousing and order-fulfillment service. Brepols promises to carry on the Hexspoor binding business as before.

Recommended binders

Belgium

Brepols

Tieblokkenlaan 2

2300 Turnhout

Belgium

+32(0)14 40 25 00

info@brepols.com

The Netherlands

Boekbinderij De Haan

James Wattstraat 4

8013 PX Zwolle

The Netherlands

+31 (0)38 4656160

bbdehaan@euronet.nl

Mathieu Geertsen

Cronjestraatt 1/3

6543 MKX Nijmegen

The Netherlands

+31 (o)24 3220337

Binderij Hexspoor

Ladonkseweg 7

5281 RN Boxtel

The Netherlands

+ 31 (0)411 657157

binderij@hexspoor.nl

Stronkhorst Boekbinders

Rigaweg 18

9723 TH Groningen

The Netherlands

+ 31 (0)50 5418789

Boekbinderij Van Waarden

Pieter Lieftinckweg 14

1505 HX Zaandam

The Netherlands

+31 (0)75 6703948

info@boekbinderijvanwaarden.nl

Germany

GGP Media

Karl-Marx-Straße 24

07381 Pößneck

Germany

+49 (0) 3647 430

ggp.poessneck@bertelsmann.de

Buchbinderei Hendricks–Lützenkirchen

Ackerstraße 50–56

47533 Kleve

Germany

+49 (0)2821 26403

henlue@gmx.de

Kösel GmbH

Am Buchweg 1

87452 Altusried-Krugzell

Germany

+49 (0)8374 580

info@koeselbuch.de

Buchbinderei Müller

Gewerbegebiet Nordwest

Ringstraße 8

04827 Gerichshain

Germany

+49 (0)34292 6190

info@bubi-mueller.de

Portugal

Gráfica Maiadouro

Rua Padre Luís Campos 586 (VERMOIM)

4470–324 Maia

Portugal

+351 22 943 97 10

dir.comercial@maiadouro.pt

Romania

Fabrik

Ceremusului 3–5

Bucharest

Romania

+ 40 (0)727 732 577

atelier@fabrik.ro

Switzerland

Bubu

Isenrietstrasse 21

8617 Mönchaltorf

Switzerland

+41 (0)44 949 4444

buchbinderei@bubu.ch

Schumacher AG

Industriestrasse 1–3

3185 Schmitten

Switzerland

+41 (0)26 497 8200

info@schumacherag.ch

Terminology, sources, acknowledgement

In Dutch, the cold-glue process is ‘koudlijm’. In German it is referred to with the term ‘Dispersion’. And in other languages? A helpful brief summary of present methods of binding, from a North American perspective, can be found in this article by Brandon Rasch. What I have written here derives largely from trade sources, such as this, which I have been able to find on the internet. Please do get in touch if you have corrections or comments. I would like especially to add to the list of binders who still do cold glue.

The original impulse for this article goes back to conversations with Karel Martens, who first told me about cold glue. Thanks, most recently, to João Doria, Raymond Bobar, and Ruben Dias for help with adding to the list of binding firms.

Robin Kinross