Some years ago – I recall events and publications in the early 1990s – there was some noise about the ‘designer as author’: graphic designers would have a hand in writing (or maybe ‘authoring’) the texts that they also designed, and designers could even be considered as authors. It follows from the technology: the text gets shaped by designers, and the last touch before publication may now be in a designer’s hands. And there is the fact that content is always embodied in its form, and so to make form is also to shape content. But it does not follow that the designer needs to become an author. I don’t believe we should give up on the ideal of the designer working hand-in-hand with an author: listening, thinking, suggesting possibilities, making changes to first proposals, and often following an author’s wishes. There are clear advantages in a separation of the two roles: designers see things that authors can’t, and vice versa. (Against all this, the arrival of another new technic – screen displays of content – may take this process in another direction: away from the hands of any designer and into the domain of the ‘browser’ and its settings, and of the particular screen that is used.)

These days the talk seems to be more of the designer as publisher, as a flurry of exhibitions and meetings has been showing. One of the main outlets of news here is the Manystuff website, which documents the flow of publications, often from colleges or designers linked to colleges. Easy access to the machines – both digital duplicators and stencil machines of an earlier moment – has helped this. The move of artists into word- and print-production is another factor. A network of small bookselling operations has come into existence, often as part of art-spaces, and they help to provide an outlet for the publications.

As I suggested in a recent post, Hyphen Press doesn’t really belong to this movement or moment. Its domain is still largely the ordinary book trade. Though, given the troubles and the limits of the ‘ordinary book trade’, to find other places for selling books can be welcome; but not always, if it means making many little deals with small sellers and then having to chase them for payments. But the qualification can be made more essentially: Hyphen was set up by a designer-writer to publish work by other writers, and in the process he became an editor. The designing that happens here is usually part of a collaboration, and one element in an attempt at integration of writing, editing, designing, and production management – into a whole circuit of collaborations.

Here one has to mention the central importance of editing, which means everything that happens between the writing of a text and its presentation to the public sphere. The editor is the often unmentioned, and often absent, middle person who works between writer and designer. On the evidence now appearing, it seems that editing is often neglected in the present designer-as-publisher processes. Designers move too fast into the final presentation; there is a cult of the found, the copied; choices and decisions haven’t been made. An editor, thinking on behalf of the material and of the public, would help to sort all this out.1

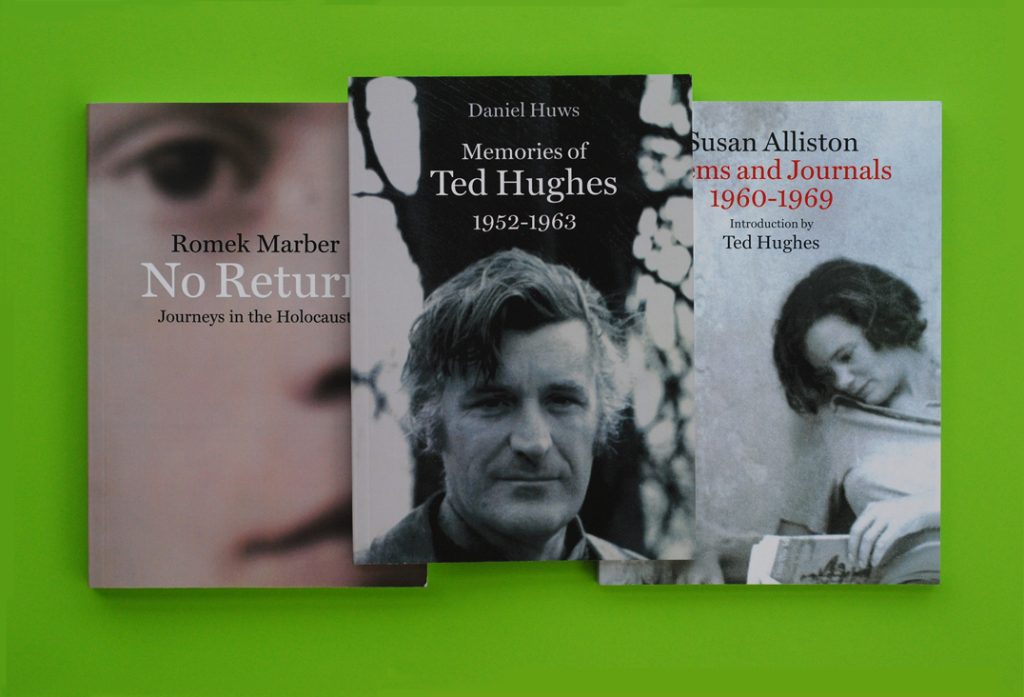

A recent designer-become-publisher provides some illumination here. This spring Richard Hollis issued three books under his own imprint. These books are not extensions of Hollis’s design practice. Yes, he designed them – but they could have been published by anyone else. Except, they wouldn’t have been; or not easily. Each one was written by someone that Richard Hollis knows or has known, and so they come out of that circle of friendship that has often been a good ground for a publishing operation. Yet each of them is entirely worthwhile, and, now that they exist as books, it would be hard to think of them not existing as books – there is a kind of inevitability in them.

This has something to do with the design of the books, which is absolutely convincing. Hollis has typeset them himself (for the longer text, Romek Marber’s, he had a collaborator) and designed them in a normative, unshowy way that any large publisher could accept, although they might find it too unshowy. The books have been ‘printed on demand’ and are instances of how good this process can now be. POD would have determined the A5 format used (and the thick-and-unbending glue on the binding). The selling prices are notably low.2

As for what is in the books … I read Daniel Huws’s memoir of Ted Hughes in a sitting, and, although a distant observer of the Ted-Hughes-biography scene, found it salutary: it has the smell of truth. Susan Alliston’s writings, again read in a gulp last weekend, are really fresh and surprising. The memoir by Romek Marber I still have to read – it looks like a book that will take over your time until it’s finished.

Notes

1 Otto and Marie Neurath spoke of the transformer as ‘the trustee of the public’. Their ‘transformer’ was an editor.

2 Correction (2010.07.16): the pages of the books are printed by offset lithography; the covers are digitally printed. The printer is Short Run Press in Exeter.

Robin Kinross