The interview that follows was recorded on 20 August 2015 in Roland Reuß’s office at the University of Heidelberg. The text has been lightly edited for ease of reading, but otherwise follows closely what was spoken.

Introduction

Roland Reuß teaches literature and text-editing at the University of Heidelberg, and co-directs the Institut für Textkritik there. As well as co-editing, with Peter Staengle, major historical-critical editions of Kleist and Kafka, he is a prolific writer on the subject of literature and editing. In addition, in the last few years he has published a stream of articles, especially in newspapers (notably the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung), on wider and more explicitly political themes: the rights of authors and publishers in the face of unlicensed copying of their work, the continuing virtues of the printed book as a means of embodying and duplicating texts and images, the role of independent publishers and booksellers in maintaining human culture.

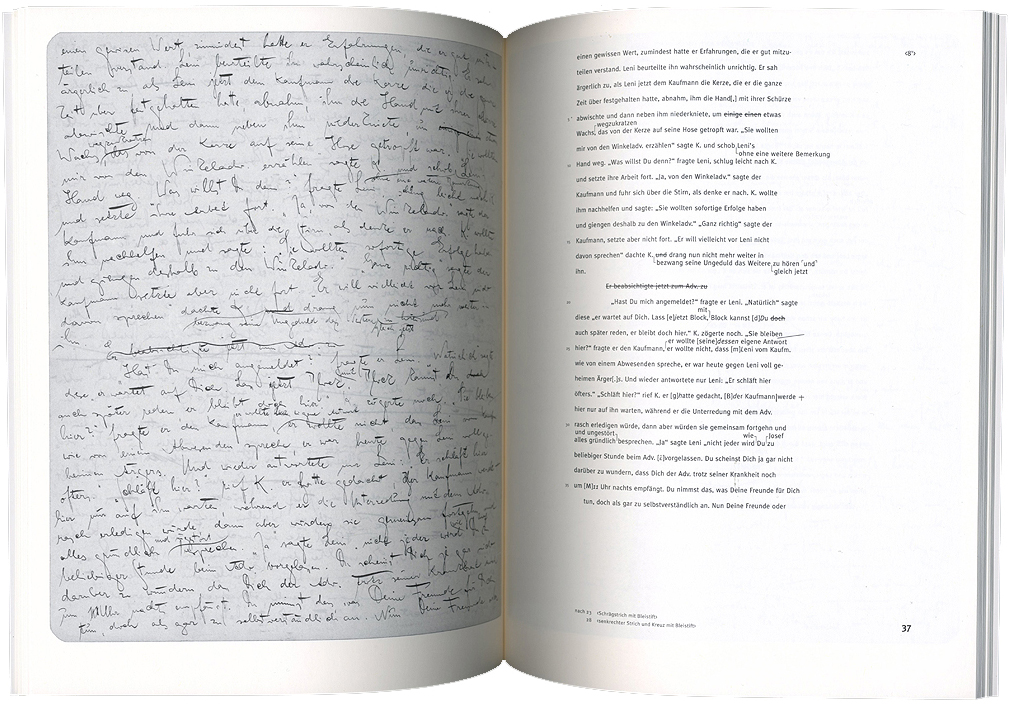

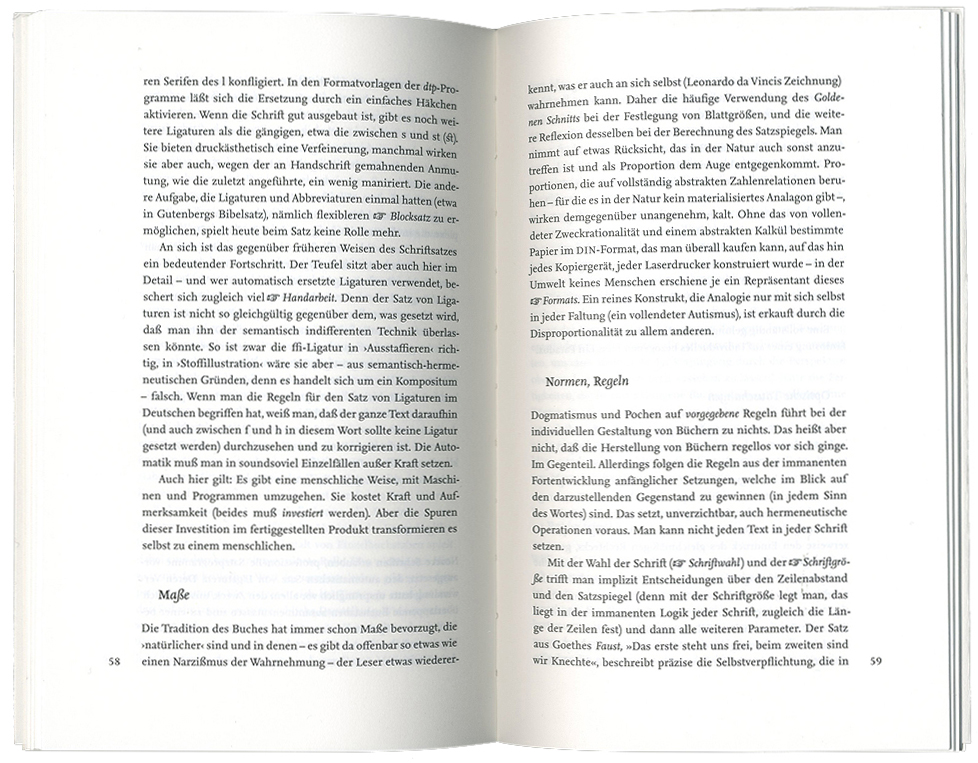

Der Process: Kaufmann Beck [Franz Kafka Historisch-kritische Ausgabe], Stroemfeld Verlag, 1997 (page size: 280 × 215 mm)

The work in making historical-critical editions that Roland Reuß and Peter Staengle have been carrying out, since the late 1980s, is remarkable in several respects. From the point of view of a typographer its most compelling feature is the fact that the texts have been set by the two editors themselves (and the facsimile reproductions of manuscripts, and occasionally also of authoritative early printed editions, are subjected to critical and technically knowledgeable scrutiny). In their design, these books are assured and elegant, and are evidence that editorial judgements and typesetting function well when they are embodied in the hands of one and the same person. It is probably true that text-setting as complex as these ‘diplomatic transcriptions’ can only be fully achieved when the editor is also the typesetter. A third figure must be named here: the publisher of these editions (and of most of Reuß’s other books). This is the Stroemfeld Verlag in Frankfurt a.M., founded in 1970 (as the Verlag Roter Stern) by K.D. Wolff, within the stream of the West German socialist student movement. As well as the publisher K.D. Wolff, Stroemfeld’s designer Michel Leiner (1942–2014) played an important role in guiding the overall shape and external features of these books.

As Reuß explains in the course of this interview, his ideas about the limits and dangers of digital culture are long-standing. But a glance at the bibliography of his writing shows that since 2009, the dangers of digital culture (to use a loose term) have come to the fore. That year saw the publication of the Heidelberger Appell initiated by Reuß and published by the ITK, which seeks to protect the rights of writers and publishers on two fronts: the unlicensed copying of work on platforms such as Google Books, and the pressure on authors from institutions supporting research to publish in certain ways (primarily, ‘open access’ online journals). Some background to this initiative can be found in Ben Lewis’s splendid documentary film Google and the world brain, released in 2013, which focuses on the court action against Google brought in New York by the Authors Guild. Among the witnesses interviewed in the film was Roland Reuß.

The following interview was prompted by the recent publication of three books by Reuß:

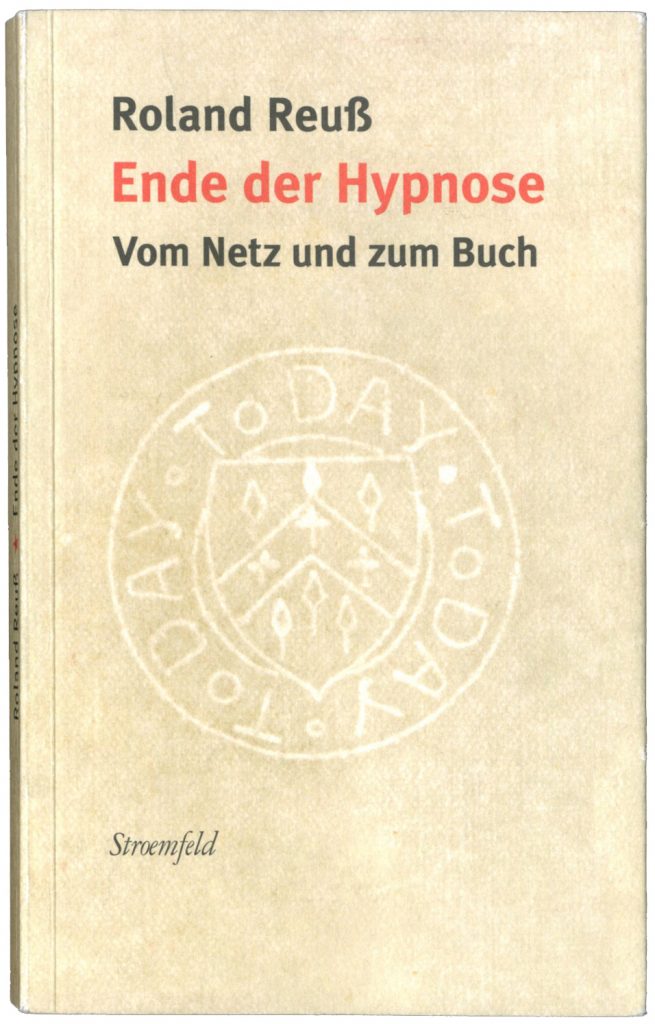

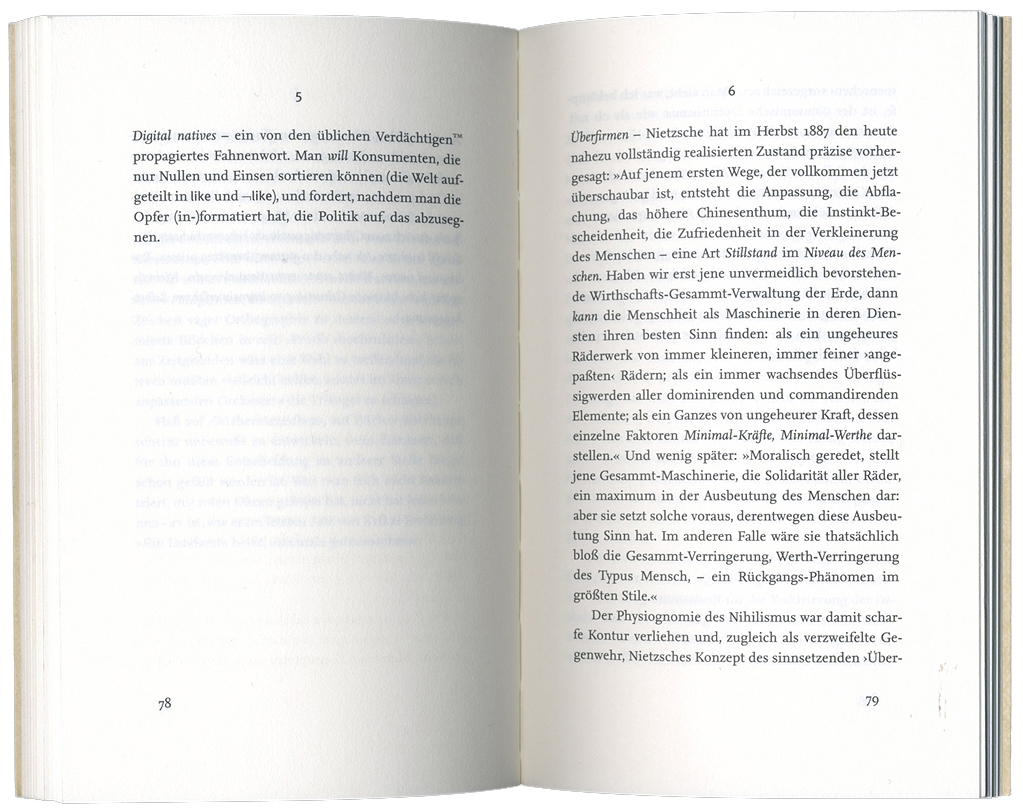

Ende der Hypnose: vom Netz und zum Buch (2012) [The end of hypnosis: from the Net and to the book]

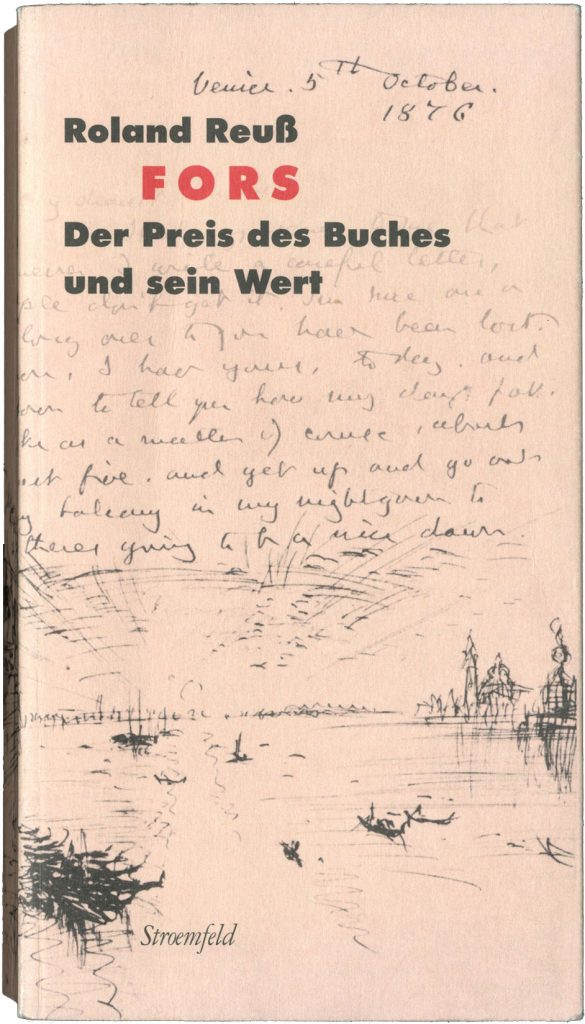

Fors: der Preis des Buches und sein Wert (2013) [Fors: the price of the book and its value]

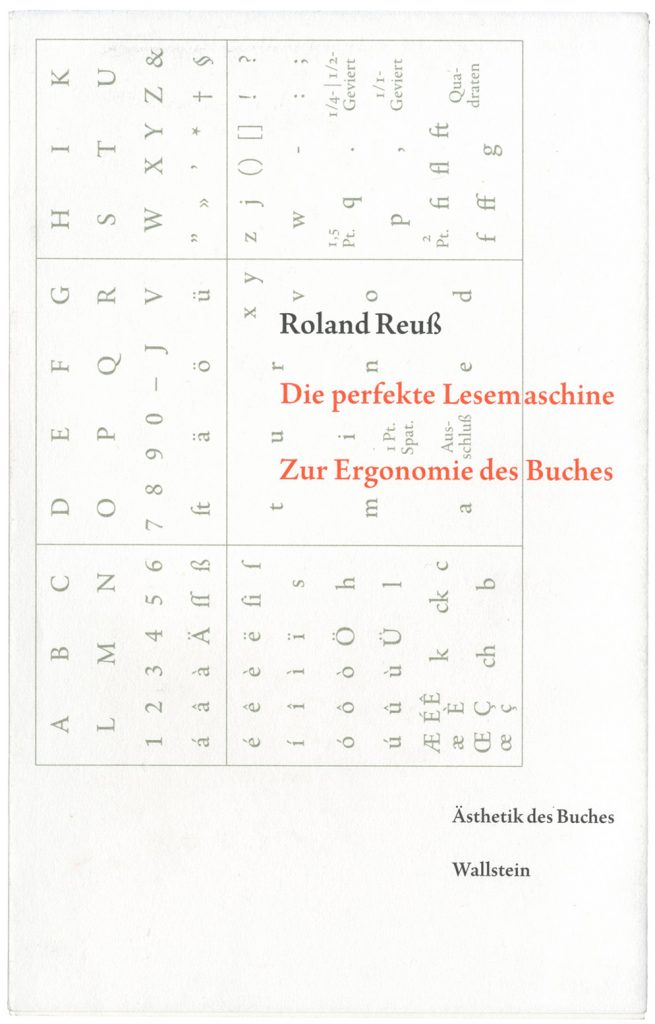

Die perfekte Lesemaschine: zur Ergonomie des Buches (2014) [The perfect reading machine: on the ergonomics of the book]

All these books are written in compressed, charged prose, and organized in short sections. They are hard to summarize, but here are thumbnail sketches.

(page size: 178 × 110 mm)

Ende der Hypnose addresses the largest issues of the present digital culture and the effects of what is known in some parts as GAFA. Against the hypnosis by which we accept these developments as all-powerful or simply inevitable, Reuß proposes the free, critically thinking individual as the origin of resistance to them; against the pervasive, limitless expanses of the Net, he proposes the printed book as a place of real freedom.

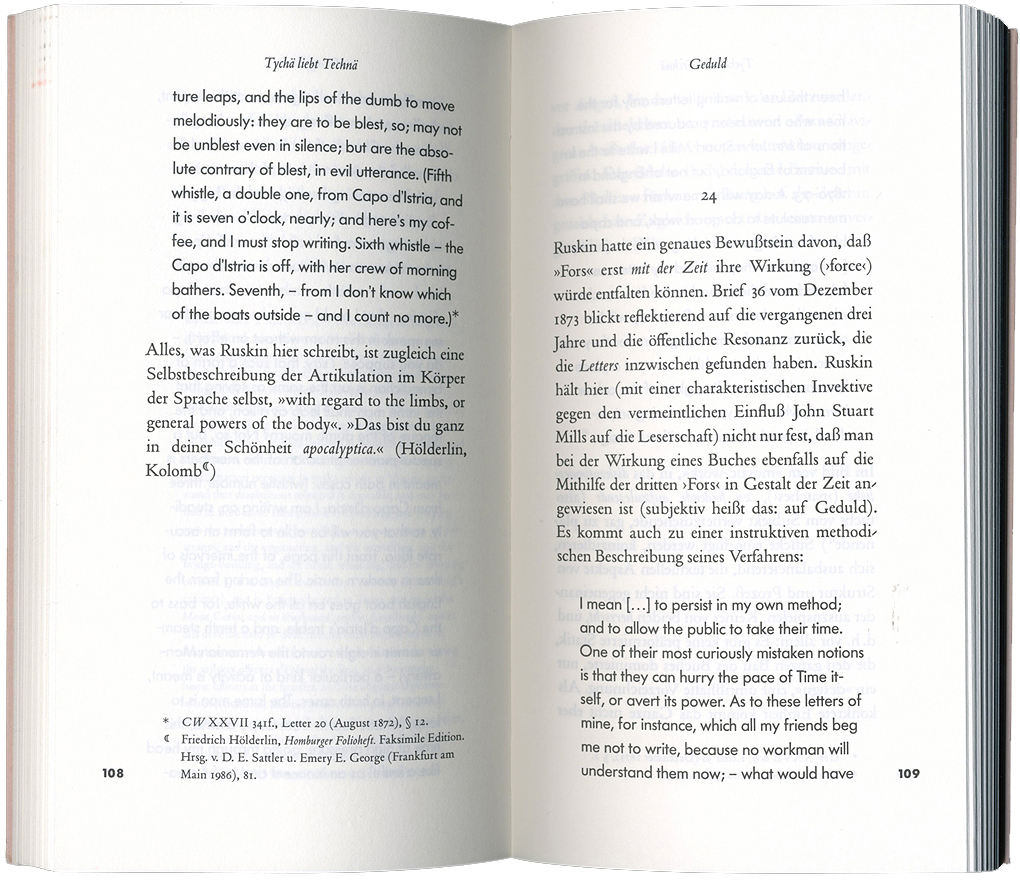

(page size: 227 × 125 mm)

Fors takes its title from John Ruskin’s Fors clavigera (the series of letters ‘to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain’ that Ruskin wrote and published between 1871 and 1874). After a prologue quotation from Otl Aicher’s description of a bookshop in the south of Germany that during the Nazi years served as a place of free thought and resistance, Reuß’s discussion moves on to some exposition of Ruskin’s concerns in Fors clavigera. A central section presents Ruskin’s entrance into the book trade, and his arguments for establishing fixed prices for books. Reuß focuses next on the value of books as bearers of human spirit, then (via Ruskin’s Venice) goes on to consider Ezra Pound’s ideas of money value, he then travels to ‘value’ as it is treated by Shakespeare in Troilus and Cressida, then returns to the book in a Ruskinian perspective. The concluding section centres on another story from the book trade in the Nazi era.

(page size: 205 × 130 mm)

Die perfekte Lesemaschine is published by the Wallstein Verlag in Göttingen within its series on ‘the aesthetics of the book’. The opening section, which began life as an essay for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung in February 2011, takes up Paul Valery’s idea of the book as a ‘perfect machine for reading’. The main body of the work is comprised of 50 alphabetically ordered short sections devoted to particular topics in the typography of books: from Apostroph (the apostrophe sign as a carrier of essential meaning, commonly lost when the false substitute of a prime sign is used), through topics such as footnotes, the work of the Lektor, type size, and on finally to Zweispaltiger Satz (two-column setting). Reuß proposes that books are always real artefacts, whose success or failure depends on the quality of their production, and on the smallest details of their design and production.

Net and book

RK: I see these three books as a perhaps unintended trilogy, although they do different things. The first one, Ende der Hypnose, came to me as a little explosion. I received the book unexpectedly – I don’t think that I knew that you were writing it – and found it very powerful, although also difficult. But I could get enough from it. You use the word Mut (courage): that’s what you want to give us as readers, and that’s what the book gave me. I can give an example of one of the things that I did following my reading: we had our Bach Players CDs available on a number of streaming services, and I then took them all away from those streaming companies. Streaming seems to me an example of the trivialization and cheapening of culture, partly through the loss of materiality. The music CD although ‘digital’ is also a material object that gives a shape and a context to whatever ‘songs’ (as iTunes terms them) it carries. So that could be an example of how your arguments have had a resonance in practice.

I remember soon after I met you in the early 2000s, you showed me how you were using your computer, for making the critical editions of Kleist and Kafka, and for the ITK website. I was impressed with your absolute competence with computers and also with making books and websites on computers. So you were already then immersed in the digital world, and were using it very seriously and intensively. But when did the realization of the dark side of the digital world come? Did you already have it then?

RR: I think it’s a problem in perceiving the means of a new technique. The main point for me is always the telos: the aim towards which you are oriented. I use everything I can to make it better. So if you are transcribing manuscripts and if you are presenting them to the public for study, and if you can have an improvement by using another kind of technique, then I will use it. But it’s not an aim in itself to use that technique; it’s subordinated to the main purpose. As long as this is guaranteed, I don’t have any problem with any technique.

But then there was an environment in which people were telling you how to do something, and were talking about the technique as an aim in itself, and using slogans such as ‘the book is dead’ and ‘if it is not published on the internet, then it doesn’t exist’. This kind of mere propaganda annoyed me very much. Then you have a lot of money in this, and with this money you have a propaganda apparatus, with which Apple, Amazon, Google, and so on, are trying to indoctrinate you, telling you how to do your job. So if you have been working for many years on these editions and you do know what you have to do, you will not be very pleased if some very strange people try to interfere with your working process.

This ‘business’ is wonderfully combined with a disrespect for creative working. That began to be clear – because these huge firms wanted to have your content for free, and that is because they want to make money with your content. That was also not in my interest, because I wanted to have complete control over my products until they reached the public.

If you have been working for twenty years and producing a lot of books, and you find your books on websites without your permission having been asked … that was very upsetting. This is not just a kind of disownment of what I have produced, but it is a disrespect. It is a very populistic thing. You are talking about giving everything to the public for free, but you don’t put forward any ideas about how to produce new content. To make some shelter for the sphere of producing new content there was a fight that lasted about 200 years before the measures were pressed into the political sphere. Then these American department stores come and say ‘OK, we do our thing, and we don’t respect your property, we don’t respect your workflow, we just get this stuff into our databases and make more money with it.’ That upset me very much.

RK: So that was really the moment – seeing your books on Google Books?

RR: Yes, but long before I saw my books on Google Books, I saw the whole disrespect for the typographic tradition, by using absolutely appalling scans. That means something. If you see they have a quota of 80 per cent of the pages scanned correctly and 20 per cent abysmally, you see they don’t respect the work of other people. That is expressed just in the percentage of good scans. That is apart from any question of moral rights.

With Google Books, the public may be missing the point. People make large data analyses and will say ‘it’s interesting to see how semantics change’. But the data is not correct. There was no quality control at all.

I happened to have this with a case from somewhere else than Google Books. It was a scanned edition of Hölderlin made by the Württembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart. They made a PDF file by using the OCR within Adobe Acrobat. In fact here the result is also 80 per cent correct and 20 per cent is abysmal. So if you are looking for phrases or words and you do not find them, it doesn’t mean that they don’t exist in this work, it only means that nobody has looked through it to check. That’s a real perversion of philological labour – I say ‘labour’, not only ‘work’! This is one of the editions that is nearly foolproof: it was corrected and corrected and corrected. I think there is no printing mistake in the whole book. But in the scan and in the OCR file of the PDF, there are so many mistakes and faults that you cannot use it. But nobody analyses it. People – including students – have talked about the lack of certain semantic fields in Hölderlin, and this is not true: it is there, but it is not re-alphabetized by the OCR. That was long before property issues were at stake. This was about quality.

I wrote an essay, I think about 1997, long before this mass-digitizing by Google Books was there, criticizing the lack of quality of this effort to get everything into the databases. This is clear, because there was a kind of conflict of aims. Google wanted to have a lot of proper names in their machine, because proper names and dates (not ‘data’) are the main currency in a search engine. If you get in a lot of proper names, you get a lot of hits. Whether the scans were sufficient or complete was not a matter of interest for Google. But for a scholar, it is a matter of great interest to have it complete and to have it controlled by a human mind, to see if it is correct or not. My last point here is that if you are in the Google database – and they put in all our works – and you don’t have any ability to correct the faults, this means that they are using your name and your authority, but you cannot take responsibility for it. This is apart from all the juridical questions that surround it.

RK: It’s a kind of impersonation: they have taken your name and your identity.

RR: Right. Just like entering and pirating a ship that you haven’t stocked yourself.

RK: So you had been writing about this before Ende der Hypnose. Maybe this shows the power of a book: you had been writing articles, but then suddenly a book comes, which really has a greater force. A book can make a statement.

RR: I think it’s a symbol of concentration. Of course, one of my main purposes was to encourage other people to speak up: not to stay calm and put your hands in your pockets, but to say that this is a development that is controlled by financial and political thinking. If you are living in a democracy, you have to be asked before somebody makes those kinds of development. But we were not asked. People tend to see it as a natural development that nobody can stop. That is bullshit, because even atomic plants can be discussed and be taken down, if you are thinking about them politically. If you are trying to suggest that this is a normal process, in which people don’t have any voice – whether they are for or against it – you are saying that they don’t have any democratic representation in this case. This is also in my book. I think it’s clear that we have to have a political discussion here – in which fields do we want this development?

The public has to be informed about the huge costs that arise with this storage of data. Nobody was discussing this. They say it’s very cheap to make a PDF file, an XML file, a TEI file and put it on the server. But then, after a while, you have to ask if it will be transferred to the next generation of file, for the next ten years. These are all decisions for librarians and such people. Nobody else was talking about this. If you print a book on high quality paper – in Germany now, every serious book is printed on good paper – you can be sure that nobody has to care about it for the next 300 years. But computer files are not in this category of being automatically available.

Afterwards I stumbled across a very interesting note about this, by an old classical philologist who was very famous in Germany in the 1960s and 1970s – Wolfgang Schadewaldt. He wrote about the preservation of the papyri at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. He said that the main reason why these have survived from about 300 or 400 years BC is that nobody had to look after them: the sand was above them, it was a good atmosphere for conservation, and nobody cared about them. Because nobody was looking after them, nobody had to make a decision about how to transfer them into the future. That is a real advantage. In the digital world you have to decide all the time. You have to make a decision to supply energy. How to deliver electrical power is a decision, and it costs money all the time. Negligence is no good in this case. Nobody has really thought about this.

For most people electric supply is quite natural; they don’t see that it is artificial. Power supply is also determined by political and social processes. There was an appeal for aid by the Bavarian state library, after they had completely underestimated the costs of the server for the Google Books project. They did not know that they were using €30,000 a month just to have the servers plugged into the power supply; they had not thought about it when they signed the contract with Google. Then there are the costs of converting files, of crashes of the system, and so on. They just thought it’s cheap, but it is not. Michael Hagner wrote a book (Zur Sache des Buches) about this whole phantom of having it cheaper: all the calculations show that it is much more expensive if you store in this kind of environment. For me the analogy with atomic plants has been quite clear. The same arguments are used by politicians: it is very cheap, you don’t have any ambient effects. But in the long run, it is so expensive – apart from any catastrophe that may occur – and you don’t know where to store the atomic trash.

RK: Can you elaborate on the subtitle of Ende der Hypnose: ‘vom Netz und zum Buch’. How does this work, ‘von … zu’?

RR: I’m playing with the ambiguity of the particles. Vom Netz means the Latin de (‘about’), and it also means a (‘from’). So I talk ‘about’ the Net and I get ‘away from’ it. Zum means a direction (‘to the book’), as well as ‘about’. Both particles mean ‘about’. I wanted to show that this kind of development is not neutral, in a moral and political sense.

The main title is borrowed from McLuhan. All the apostles and heralds and messiahs said: ‘we have a new kind of media, a revolution; and as with every media, it is neutral, the question is only what use you make of it’. These people don’t like the citation from McLuhan, who says ‘that is not the case – it is not neutral, and you have to evaluate it very carefully, and you have to say you want it, and not say it is just a natural development that nobody can stop’. [McLuhan, Understanding media ] If you say this about anything, you cannot be a political person. This is so even with climate change, which is, in a way, ‘natural’ – but people are the causes of that. So that too is a political question, not just a natural process. If you say that you cannot have a stand on these questions, you abolish the whole notion of politics.

RK: I don’t think I have read any reviews of the book, but I have picked up some sense of the reception of it, perhaps through conversations with you. There is a certain mentality that I know from life in Britain and which I think is also directed at you. A quality you have as a writer is of a certain fierceness or sharpness, which people will dismiss as exaggeration. They will say: ‘he’s going too far – calm down, things are not so bad’. I remember from the days when I studied literature, around 1970, one of the great figures, then still alive, was F.R. Leavis. He too had this fierceness of attack, and he was frequently dismissed as a crazy moralist. Later on I read Adorno, and found the same quality. Now you have brought Ruskin into the picture, and he has the same moral attack. This is the landscape in which I see your writing. I could quote a typical sentence to illustrate what I mean – it’s from Die perfekte Lesemaschine (p. 48) ‘Ohne Markierung in der Materialität gibt es kein Kriterium.’ You are writing about the essential difference between text on a screen and text that has been printed on paper, and you conclude with this thought: ‘Without a material marking there are no criteria [for evaluation].’ Or I remember your words about Google: ‘Der verlogenste Ort im ›Netz‹ (und es gibt viele verlogene Orte dort), zugleich das Geheimnis des Erfolgs von Google™, ist die Startseite der Maschine.’ [ Ende der Hypnose, p. 25] To translate: ‘The most mendacious page on the “Net” (and there are many mendacious pages there), and also the secret of the success of Google, is the home page of the search engine.’ It is such an absolute –

RR: – pointed!

RK: Yes. People will say ‘don’t be so extreme’. How would you reply?

RR: In fact I’m not anxious about that. Ende der Hypnose was published in 2012. At that time there was no NSA scandal [Edward Snowden’s revelations] and nothing else of that kind. People were a little aware that it might be complicated if your email account is being looked at, and so on. Back then I prophesied that nobody should be surprised if it turned out that Google and the other IT firms were collaborating with the CIA. People in 2012 said it was an exaggeration, but it was just a year before everyone could see that it is this kind of development and it was going on when I was writing the book. It was an intuition.

The main problem is that everyone is compromising with the system. You can compromise, but first of all you have to make the points very clearly: zuspitzen – concentrating it just in a sentence, a gnome [γνώμη] as the Greeks called it. It is very useful in starting a discussion. At first you need to see something sharp. People always blur the horizon, whether they are using alcohol or catch-phrases, and then they cannot see a sharp line. If you look at the the whole society of the West, the apathy there is one of its main political developments – not through any one person’s intention, but it is in the system: the wills of the people are made dumb. To stimulate the will, even if it is a counter-will, you have to articulate your will quite pointedly. I was writing it in that way.

RK: Yes, it’s a way of thinking and writing, with a certain aphoristic quality. I find it absolutely convincing.

RR: Let me say this, because it’s important for the way of writing. Kafka is an exemplary case of it, and in my view Ruskin is the same. There is a kind of methodological foundation in their writing, which is directed against controlling. As you see, all societies in the West aim at control. This is a kind of literature which is against control. My writing has not been planned: I don’t have any concept before I write. I do have ideas. But then I wait and see what comes in front of me, and I respond to it. It’s not so much an active writing with planned concepts which are then executed, but it’s a responding writing. It’s more free. The main thing is about waiting, then responding – to other writings, to political developments, to technical developments. This was interesting in reading Ruskin. He has a theory about this: it was not his mind that acts, but he responds to things that come into his mind.

This fascinates me, because it is much more sovereign. If you want to control everything you are completely unsovereign. Then you don’t have any hope, because the order is determined, and you fear anything that is not controlled. You see this now in all the political systems of the West, and in the East more or less too. Literature is perhaps the only field that is not controlled by any system. With literature, you cannot force an understanding.

In the last five or six years, I have read all the 39 volumes of the Library Edition, before writing this Ruskin book (Fors). You know he has depths and also surfaces. It is very interesting to see how spontaneously he writes – not at all controlled, as you might think of a Victorian. I sympathize with him because he was so able to stay with his faults. If he makes a mistake, he does not try to retouch; after a while he says ‘that was a fault to do it like that’. That’s so charming. I don’t know who read him, but people did read Ruskin all the time – or at least they bought his books. I can’t imagine how an audience read Fors clavigera. It’s so personal and strange, for that time.

RK: When did you discover Ruskin?

RR: I think I discovered Ruskin by reading Proust. You know that Proust’s first steps were to plan a translation into French of The stones of Venice. His mother bought him one or two volumes of the Library Edition, and Proust reacted to this – all the descriptions of Venice in the Recherche were written under the influence of Ruskin’s Stones of Venice. I thought that it must be interesting to read Ruskin. I went to our university library in Heidelberg and I found that it had the Library Edition, offered as a gift by a then famous American, an emigrant from Germany to the USA in the 1850s. I tell the story at the end of Ende der Hypnose. I found it so significant: you make the Library Edition of Ruskin a gift to the university library of Heidelberg. That’s a kind of old Ruskinian thinking, that there is no force, no contingency in it. There must be a kind of sense in it, that I stumbled across this edition here. I must have been one of the first to read it at all, because many pages were still uncut. I think I had it on loan for four years, without anyone else asking for it. I had the whole edition under my ownership for that time. You develop a special relationship with that author, because you know that you are the only person who is reading it here. Afterwards people began to go to the library to look for it. So I did have some effect here.

RK: Your book certainly got me reading Ruskin again. When I started with typography as a student, I found this lineage of people – the Arts & Craft lineage: Ruskin, Morris, and others, including Gill. I could mention also Lewis Mumford, who took something from Ruskin. So that was my first period of Ruskin.

In Fors you focus on a perhaps lesser-known aspect of Ruskin’s activities – his campaign for fixed book prices. Ruskin helped to establish agreed prices for books in Britain, but our Net Book Agreement was abandoned 20 years ago. Now the general view here might be that books should be freely priced, just as any other goods. Can you explain in a nutshell why you feel it is essential for books to be fixed in their price?

RR: Books are not only commodities, they are also cultural objects that should be protected. So they do not only have a price, but – this is a distinction you can find elaborated already in Ruskin – they do have a value, too. Hence the subtitle of my book. I found it not only interesting, but also necessary to go back to the roots of protecting this value. Nowadays we have Amazon which openly declares that it wants to destroy the fixed price we have in Germany and in France. Their aim to erect a monopoly is blocked by the fixed price, and as long as we have this, the precious existence of the whole structure of smaller local bookstores all around the country is, more or less, guaranteed. So this is an important battlefield. Sometimes you can celebrate a victory, as we did after Amazon had sold me, by accident (in every sense of this phrase), a new book with a discount of 35 per cent – we went to the court in Luxembourg and won.

Getting more and more into Ruskin I discovered that he was confronted with a similar situation. There were the large bookstores in London, Manchester, Liverpool, etc. and by giving a huge reduction on the bestsellers they eliminated the basis of mixed calculation which is essential for smaller bookshops. You sell 12 Dan Browns and with that you can compensate the losses with books you don’t sell so often. Small publishers act in the same way. It’s a system of economic solidarity, not rogue capitalism. It is necessary to be able to offer books in your store, which are not bestsellers; the same economic logic applies to publishers. This especially is the reason why you visit your local dealer: you can hold a book in your hand that you didn’t know existed. The target for Amazon is quite obvious: first to eliminate the fixed price, then give immense reductions as special offers, when the next J.K. Rowling, etc. comes out, and, as the intended main effect, destroy the economic basis of the local stores. Then, when they are vanished, Amazon can fix the price as it likes. And all at the cost of diversity and for the sake of the mainstream.

Ruskin was the first to think carefully about this and in the perspective of his idea of solidarity. He decided to break this dangerous tendency of streamlining by unilaterally forcing the bookstores to offer his books across the whole UK at exactly the reasonable price he fixed. If a bookstore was nevertheless found to be offering a reduction, all deliveries to them were stopped. This was the successful intervention of a courageous writer and publisher and with it he gave a powerful example for others. Under his spiritual influence, at the start of the twentieth century, the British Net Book Arrangement was made. Like other aspects of his thinking this was then genuine Labour policy. And like so many other ideas of Labour it was compromised by Blair twenty years ago. As the argument in Ruskin is so clear I took the chance to explain to the German public what we have in our Buchpreisbindung. It’s the antidote to the ubiquitious atomistic thinking about economy.

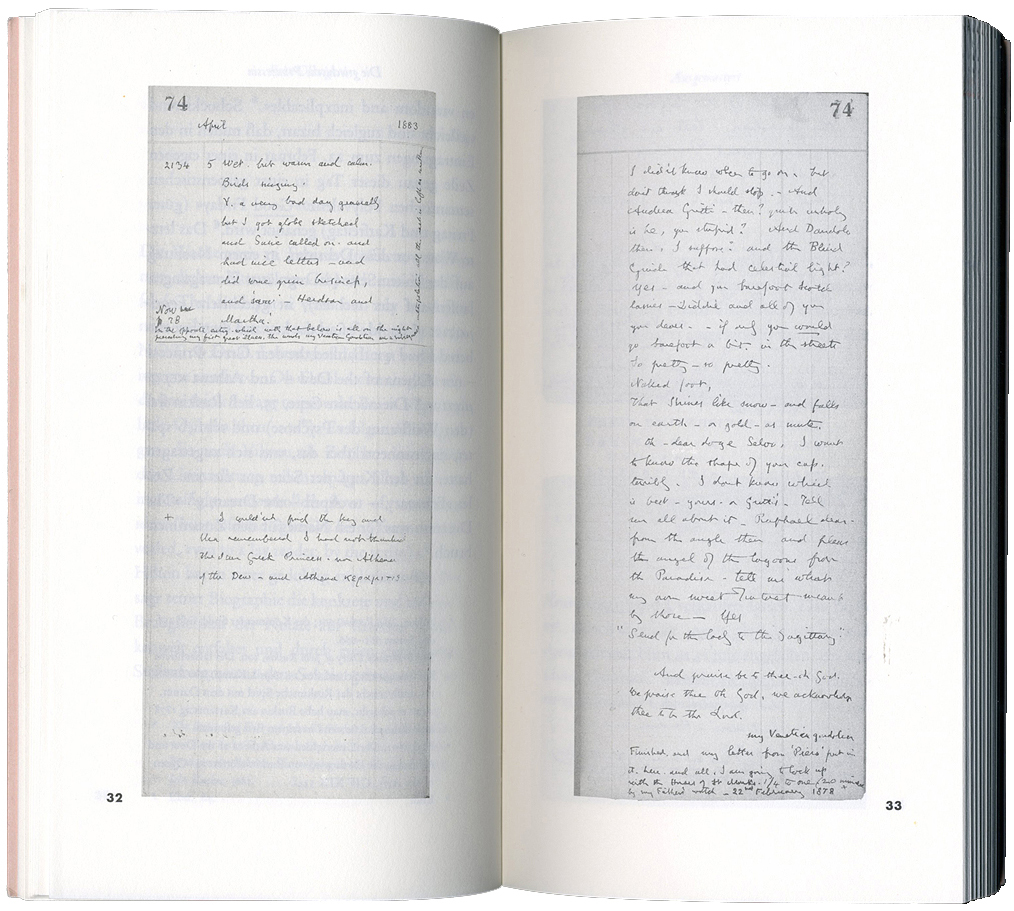

RK: As a writer you are unusual in your ability to design and construct the pages of your books yourself. This book Fors delights me as an example of the activities of writing and designing going hand-in-hand. First of all, where does the format of the book come from – is it the format of the original Ruskin Fors clavigera?

RR: One of the main problems I had was this. In the Ruskin Nachlass at Brantwood there were the last diaries of Ruskin, discovered and edited by Helen Gill Viljoen, and then bought by a library in the USA. These diaries have a special format – very tall and slim. Ruskin was using a ledger book for this, and the format is that of a typical accounting book. The decision to show two important pages from these diaries led to the choice of this format for my book.

Concerning the choice of typefaces: I found it interesting to confront the two main developments in type design of the 1920s. For the normal text I used Monotype Poliphilus, developed under the direction of Stanley Morison in an early experiment in reviving old types. For the long passages of quoted text, mostly English text – I very often cite whole pages of Ruskin (by intention) – I used Renner’s Futura. It is quite an interesting mixture. You see a clear difference between the quoted text and my own text. It’s very readable – I was astonished at how good Poliphilus is in the footnotes. It is not so cleaned up, so Californian, as you have it in the Adobe Library types.

RK: It happens also in the Ende der Hypnose: you have two typefaces, a serif and a sanserif, and there is a dissonance between them. In that book you use the Nexus Serif, but then instead of Nexus Sans you use Meta for the sanserif.

RR: The difference or contrast was not so clear between the Nexus Sans and the Nexus Serif – I didn’t like it. In Germany, this is a long tradition; it is even there in handwriting. If you have a Fraktur book, from the baroque times up until 1920 or 1930, you always have citations from other languages – even just a phrase – in an Antiqua (roman). What I have done is analogous to this. It has become quite common in books to combine Grotesk and Antiqua. You have to be careful not to over-pronounce the difference, but also not to under-pronounce it. It’s an interaction between the typefaces that you might use for the ‘strange’ text and for your own text.

Both these typefaces, Poliphilus and Futura, are in some ways the result of the tradition that comes out of Ruskin. The intermediary here is William Morris, who attended lectures by Ruskin, and who stimulated the Arts & Crafts movement. A lot of thinking about the place of hand-work followed, and you can include Stanley Morison in this, and also the Bauhaus, which transformed the Arts & Crafts ideas. This was a kind of subtext in using these typefaces. Times Roman wasn’t a real candidate here. If you enlarge Poliphilus on the screen, you can see all the irregularities, even in the digitized version. Monotype rendered the contours very carefully, maintaining the irregularities of the metal version. It makes the whole thing absolutely lively. Another one, which I also like, is the Janson typeface. These typefaces have strange irritations, subliminal to our consciousness, which keep your reading process alive: that was one of the main things for me. Poliphilus is also a very black typeface – the Nexus Serif is more grey. I wanted to do something strange with this contrast. In fact my orientation came from specimens that I have seen of the original Poliphilus, from the 1920s.

RK: I can feel your pleasure in using the reference signs for the footnotes.

RR: I didn’t want to have numbers for the footnotes, and also wanted to use them page for page, not as a sequence through the book. So I thought about having other kinds of sign. Footnotes in this book are so essential for understanding the text, that I chose to have them at the foot on the page, and not as end-notes. On the other hand, in Die perfekte Lesemaschine I decided not to have any notes: I tried to write it as a complete main text, not as a text with scholarly material underneath on the foot of the page.

RK: Another thing I could point out in the design of Fors is the running heads, which are phrases summarizing what is on that page. For me this becomes a moment of pleasure, not so much that it really helps you in ‘the machine of the book’, although they perhaps do that to some extent. It’s so different from the convention of having the same thing on every other page.

RR: In German we don’t say ‘running heads’ but lebende Kolumnentitel: living column titles. This is complete handwork – I wrote by typesetting. I had to decide what was the running head for this double-page. It was a fun to do this. And also you cannot automate this. It’s a kind of signal of the whole spirit in making this book.

It’s clear that you cannot foresee what will be on the pages and write these in advance. I had it in InDesign and looked at the double-pages and thought about what would be a good ‘living column head’. So this was all hand-made. And this is an intelligent use of digital means. It is for the human being – and not the human being for the digital apparatus. You use the means to make the product much better.

RK: It’s a great example of this idea.

RR: In fact it’s a kind of parable: you can now print perfect books. If you look at the advance of kerning, which was always a design fault in metal printing type, you see that the kerning problems have gone. But just when you can deliver perfect typography, the American IT industry wants to abolish books. It’s a paradox.

RK: While we are talking about details, you do this thing of letting some capital letters extend out into the margin, for example the V. I don’t see it done much elsewhere. Is that in InDesign?

RR: Yes, it’s there. You can also do it with hyphenation signs. You get a more compact setting, more Spielraum between the words. If you study incunables you see that the technique was used in the fifteenth century. They were very aware of holes in the lines. It was interesting to see if I could achieve that – although it may seem too ‘snobby’. You see in the incunables the hyphenations are at about 45 degrees, and that’s because they wanted to make the text area equally filled with ink. They even used double hyphenation signs. In the Poliphilus there are diagonal hyphens; also in Bruce Rogers’s Centaur typeface. In this book there are a lot of hyphenations because the lines are not very long, and so you have to be careful to use the right hyphenation sign. I think I even intervened with FontLab to improve the Poliphilus hyphen sign. It may be forbidden, but I did it for the sake of art!

RK: Can I ask you about Stroemfeld and your relations with this publishing house? This relationship must also make possible the freedom you have in making books and in publishing them.

RR: Yes, we gave each other encouragement, reciprocally, to go to the public with these books. Also, it is to defend a certain publishing culture, with small publishing houses. I think they are a fortress against all the encroachment on individual freedoms – also they are a shelter for authors. You can see in Amazon, also in Google, that they don’t want to have publishing houses. Of course, you do have the big publishing houses (Elsevier, Random House, and so on), but they are just conglomerates that try to integrate all the little publishers. But these small publishers are absolutely necessary for the cultural landscape, because they can experiment, they can make interesting investments without having to ask consultants, and without all the bullshit of being told how to do something by people who don’t have a clue about how publishing works.

We discuss the books for their content (so-called), but also we discuss them for their design. For me it is absolutely necessary to have an early feedback on what I am writing. I am not so dogmatic to think that what I am doing is always absolutely good – I need people to say early on that I have to include this idea or exclude that one or put it in another place. That is essential in improving a book. This kind of ambience of five or six people who help you to get this done is for me absolutely necessary. Any author would enjoy this. Big publishing houses are not so ideal for me, because they are very anonymous. They tell you when you have to deliver, and so on.

In fact the book Ende der Hypnose was delivered finally as a PDF file I think two weeks before it was printed. There was not even an announcement of the book in the publisher’s catalogue, to say that it was coming. We just decided to do this. You cannot imagine this happening in the Suhrkamp workflow: you would have to announce it one year before it appeared. You cannot make an intervention within that horizon: it is too rigid to act fast.

There is a kind of friendliness in this. You know that you are acting together. Also these are a kind of meta-book: books about books, about book-making, about the book trade. It is quite clear that the publishing house knows that you are fighting for it. You get a different kind of interaction here than when you are preparing a new volume of our Kafka edition.

If you are a cultural minister in any educated state of the western world, you really have to spend money in cultivating independent publishing houses. It is absolutely necessary for societies to have this. The risks are minimal, but the chances of getting new ideas through the sphere of independent publishers are great. All this sinking of money into libraries, using them as digitizing machines, is complete bullshit. This is not a cultural investigation. It’s stupid to think that you can give cultural property away free, when in doing that you destroy all the publishing circumstances – and then to think that this is good for the public. That is not proved at all. It is just a saying. You have to be careful, just as much as with the car industry, that you do not demolish the production of new ideas. They are not aware of it. It’s like a schizoid official plan. Industry of every kind is put out of the house. The state does not make electric cars – they know they couldn’t do it as well as a private firm. But in the digital field, they have this splendid idea of giving the money to the librarians, so the librarians can build publishing houses. But librarians don’t have any experience there; they don’t have a clue about how to reach the public.

I’m now writing a little book about the new idea of the public. In the 1960s, Habermas wrote his most impressive book, the Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit (Structural transformation of the public sphere). Now you have quite different ideas of ‘the public’. People say that if you publish it on the internet, it’s in public. I don’t think so. ‘Public’ means also that there is some resistance, which you have to fight. If it is resistanceless, then you should be aware that something is going wrong. You cannot have an impact on a normal website if you are just putting something on that website. You may call it ‘publishing’, but it is not publishing.

RK: What do you mean by resistance?

RR: If you don’t feel a resistance to get something done … Öffentlichkeit is a fighting concept. When we put up our Heidelberger Appell in 2009, fighting for the moral rights of authors and publishing houses in producing books and anything else that has been written, I decided not to write any article on the internet. I decided to publish only in the newspapers. That made our enemies most angry. The newspapers, especially the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, which was developing in a perhaps unexpected way – it was always a conservative paper, associated with the power blocs – was very aware of the dangers of the process. I thought that if the FAZ publishes an article of mine it means that at least 20 people are prepared to defend this even before it is published. It has to go through this decision-making process before it is published, and the power of the written word is then completely different. If you simply publish it on a website, it costs you nothing – and it also means nothing.

We had a huge counter-phenomenon with a website that was a parasite on all the German feuilletons – Perlentaucher. They were very angry with me, because they use all the copyrighted texts in extracts and make a living with that. They produce nothing themselves, but take from other people without paying. The Perlentaucher pages come up early in the morning, and then two hours later they are mirrored by Der Spiegel. One day I wrote an essay in the FAZ and they insulted me – in a juridicial sense – very severely. I didn’t react; but I realized that they were mirrored on Der Spiegel, and they then altered the text. And after a while Perlentaucher then altered the incriminated text too. You see in this that nobody has a responsibility for the stability of the text.

You learn a lot about the market through these things. When we put up our Strafanzeige [charge] against Amazon, then Amazon decided to abolish my name on their website, for two weeks. No book of mine, not even a book I had edited, was available on the Amazon website. It’s a kind of censorship. I had feared it, and had written about it – that it’s very easy to eliminate by MySQL command certain aspects of knowledge, and also authors. That was a kind of prophesy, because they really acted it out.

I think it’s necessary that people understand the dangers of this kind of ‘information economy’. It won’t happen, but if you fantasize that we only have digital material left, then it will be easy to see that whole areas of knowledge can be excluded. If you eliminate a word from the search engine, then you cannot get access to it. So you don’t even know that it exists. In normal libraries of books, that is not possible. You cannot just say ‘these two metres of books by a certain author – Gogol, for example – we do not wish to have in our library’. Or you can, but it’s a complicated process. But just to have ‘Gogol’ as a stop-word in your search-engine means that you cannot search for it, and so you cannot find anything by Gogol. That is a very dangerous scenario, and, if it is possible, then I am absolutely sure that it will be practised.

RK: In your recent writings you suggest a paradox, that the great digital culture of the internet serves to prevent new ideas. It is very good at keeping old ideas alive, but the really new things it doesn’t encourage.

RR: It’s a dialectical thing, in the Hegelian sense. The main point is that the internet is like a huge exaggeration of the Allgemeines, the universal. It is global, and so on. On the other hand, it isolates people. If you isolate people, you make them aware of their powerlessness. You need the whole intermediary layer – publishing houses, newspapers, and so on – between the isolated individual and the universal, in order to have a relay between the two. Everything that eliminates this relay – and this is the wet dream of every politician and every American IT corporation – everything that eliminates this in-between is a hindrance to new ideas. If you want to propagate a new idea, you have to take a risk. But if you are discouraging individual people, because they are atomized and feel powerless, and they cannot interact with other people within the same sphere of interest, then the only thing that is generated is the mainstream. You have this in the field of science, in the humanities, in politics. If everything is mainstream, other things are not encouraged and do not develop. This was so from the very beginning of the internet: it started as a military system. That means, more or less, that there is a political interest in it. Also there is an economic interest in it, because of the huge investment in it – in the huge machines of the servers, and in the software industry behind it. This has to be recapitalized. So it is not, as people think, a ‘free’ medium. I wrote about this, even before what happened in North Africa (the ‘Arab Spring’) – the revolution that people said was caused by Twitter and Facebook. These things may help people to get into contact with each other, but they also help the apparatus to control you. From Twitter and Facebook someone can see where the next movement on the streets will begin. If you don’t have any other kind of information apart from the internet, then it is very easy for a government (as in China) to cut off channels of communication. What do you do then? You are completely lost. But in fact you can still have a kind of samizdat interaction, and now the samizdat takes the form of books! Yes, in some ways that is true. It’s a kind of chaotic distribution system, which the power blocs may be aware of as a danger. They try to stop it, and now they do have the means, by having digital equipment.

I can give you an example from the university field. A lot of money is put into open access digital libraries. There is still a flourishing publishing scene, and there are still independent publishing houses; people are not forced to do this kind of digital publishing. It is not very attractive to do it, because you get lost in the data-mining field. As long as more money from the state is put into this open access system – as much as is needed – there is no problem to publish everything that is produced in the university. But if you demolish the publishing houses and build up a monopoly in open access publishing, then the costs for the authors will rise. It’s a paradox that authors have to pay for their articles to be published on open, ‘free’ access. This is about €2,000 for a standard article. Further, there will be committees from the university passing judgement on whether this or that student should have their work published; they will be passing these judgements on the students of other teachers. Then only compromise will rule. Compromise means mainstream. If you have an interesting idea that nobody can immediately understand, it will not pass through this system. In our present system, you would go to a publishing house that is known for publishing eccentric ideas. But you don’t have those in the open access world. It is fatal, and against any scholarly interest.

RK: Do you feel any pressure to publish in certain journals? I know it from colleagues in the UK, who may be told that some journals don’t really count – they are not peer-reviewed, for example.

RR: For me, personally, there has been no pressure to publish in certain journals. But we didn’t even have a journal to publish the things we were thinking, so we had to invent one and then build it up [the journal Text]. It is now quite established. So I don’t feel this – but then I have a political publishing house to work with. On the other hand – and this is much more important – if you are editing texts for long-term use, then you feel a lot of pressure. I am thinking of the foundation board of the Robert Walser edition. They have been talking about state of the art standards, which must be fulfilled. This means you don’t have to produce books. They think ‘state of the art’ is to produce databases. That this is ‘state of the art’ is an absolutely supernatural intuition, because there is no testimony for it. It is just a catch-phrase that they have found in the atmosphere, in order to have control of the enterprise. Even the CEO of the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds was quoted last year in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung as saying ‘a book is not public – “public” is what is on the internet – a book is private property’. There are idiots of this kind, responsible for the policy of a publishing tradition. They are so dogmatic and stubborn; they don’t even want to discuss it.

If someone is working on an edition of Kafka or Walser or Musil or even Shakespeare, and he spends 10 or 20 years in doing this, then he will be absolutely clear about how this will be published. You don’t suddenly intervene in this decision. To tell him how it must be published is not a rational procedure: you want to have excellent research but you are treating the editors like children. This is in Switzerland, but in Germany it’s more complicated. I know from Swiss colleagues that the attitude there was ‘let’s wait and see how it is with the Germans: if they drive their car into the wall, then we know not to follow them’. Now it’s the other way around: the Swiss try to anticipate developments and try to be there 10 years before the others. But that means they just jump over the whole process of discussion. And this is absolutely necessary in a democratic field – to have a discussion process. There was an internal evaluation of the grants made by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and the stability of digital projects from 10 years ago. I think only 20 or 30 per cent could still be found on the internet; the others had vanished. That’s also a legal problem, because there is a responsibility in giving money to these ruins, before they vanish completely. They had not thought about it. It was just a kind of fashion.

It’s as if there is now a GDR in the field of the spirit or the intellect. In the 1960s Walter Ulbricht had a slogan, when he looked at the West German economy: ‘überholen, ohne einzuholen’ – ‘we have to overtake them, without getting equal with them’. It is not possible suddenly to be one step in advance! But this is the kind of mantra that is being followed now. It is not reasonable. What would be reasonable with a new technique in the publishing field is to give room for experiments with it. After some time of observation, you might see that for certain uses it is good to have this, for other things it is better to have that.

If you talk with physicists, they will tell you that when something is published it may well be already out of date, and that what is new is what is being discussed on their lists and forums. That is an interesting point. You can say that there is a factor of time. It has to be fast. But even in this field, you can think of research that is not under this pressure of time. If you are a historian of scientific processes, you need stable data to be able to say how physics has developed in the 1980s. If you say it is all in digital form, it is not stored, and you may say that is not relevant – but that means not relevant for you. For a historian of science, it is relevant to have this documentation. You are not producing something just for yourself. You produce it not just for physicists, but for mankind as a whole. There are such small horizons at work in these discussions.

RK: You never know who will be interested in something. There will always be surprises.

RR: Right. There is a stupidity here in the disrespect for the science of the nineteenth century. We know from experience that a branch of science that might be obsolete in 1920 becomes of interest in 1950, so you have to be able to get back to the old work. This is common knowledge. But if you only have this subsidizing of the mainstream you put it at risk. I should be able to expect from a responsible politician in the cultural and scientific field that he is educated enough to know this, and then that certain decisions should follow from it. But what we see is the attempt to control developments, rather than to cultivate diversity and difference. It’s stupid. You must give room for development.

RK: You have already answered my question ‘what are you working on now?’ It’s a book about the Öffentlichkeit.

RR: There is one fortress now against all the information technology corporations – Google, Amazon, and so on – and that is the newspapers. The newspapers are under huge pressure, because of the loss of advertising. They are also compromised, by working together with Amazon and Google. If you see that the Guardian website is on Amazon servers, you will worry about what the Guardian ’s attitude to Amazon might be – in the possible case that it needs to become aggressive towards Amazon. In the discussions of the last 10 years, if you only had the internet and not the newspapers then you would be lost. Because on the internet everything is made relative and put on one level; you don’t get any force of a political kind. Newspapers are absolutely essential. There was a very isolated article by Habermas, five or six years ago, in which he said that even if newspapers don’t have any business model, it would be in the democratic interest for the state to fund them, because it is necessary to have a critical voice against developments which otherwise we will just complain about, after the event. So it is necessary to have this kind of public sphere, which is not the public sphere of the internet.

Everybody knows that there have been commentaries paid by the Russians, and there have also been commentaries paid by the Americans and the British. But every corporation that has enough money will have paid commentators, and they give a simulation of a public sphere. But that’s not a public sphere. All the things that are anonymously posted don’t count for anything. It’s a kind of symptom, like an allergy. It’s not a real public voice.

RK: What was the reaction to Habermas’s proposition, that the state should fund newspapers?

RR: It did not carry much weight then. But I think we will come back to it – we have to come back to it. One difference between Britain and Germany is that we have a lot of different broadcasting stations, because the state is composed of different Bundesländer and they all own one. So you have 14 or 15 different regional stations; there is also Deutschlandfunk and Deutsche Welle, the national stations; also ARD and ZDF. These are all controlled by administrations that exist in a political setting. They also have websites that make competition with the private publishing houses. But they were not established to get into the printing sector, or, let’s say, into the written sector. Whether they have the right to do this has now become a legal issue, treated in the highest court. This is another kind of overtaking of the publishing system. With all these things it’s clear that there is an attempt to control public opinion. If you look at the constitution, then this is unconstitutional. Because the constitution encourages different public voices, and seeks to avoid the situation of just one public voice – a dictatorship, even if the system is still called a democracy. Then it’s clear that you get only controlled information.

RK: That’s the objection to the state becoming involved with newspapers.

RR: Right. Of course the state cannot subsidize the papers directly, a procedure which will damage their independence. But indirectly, for example by abolishing the VAT on them completely and by means of tax legislation in general, it can and should do this. It not only strengthens a forceful free public voice, but also guarantees independent gathering of information. The FAZ, Die Zeit, also Der Spiegel and the Süddeutsche Zeitung – these four papers – have a net of corresponding journalists all over the world. They are collecting independent information, and not the information that comes through diplomatic channels and the ministries of foreign affairs. If you want to be informed about what is happening in India, it is not sufficient just to listen to the official voice of the ARD and so on. That is just filtered through decision-making processes that have political reasons behind it. To get independent information – which is necessary as a citizen in a democracy, to make your own decisions – you cannot leave it just to the public broadcasters. You need other channels, to relativize what comes from the official channels.

RK: We see this in Britain too, and there is a lot of discussion about the BBC. There is what is called the arm’s length principle: the state is at one place and the BBC is at another place, and there is the length of an arm between them – with freedom given to the BBC to do what it feels is necessary. It’s never a settled relation.

RR: It’s always a battlefield! Nevertheless, there is a dialectical thinking here, formulated by Hegel: das konkret Allgemeine, the concrete universal, becomes richer with the more differences that it can cover. If you see that the whole development goes to make opinion uniform, as a responsible politician you have to find ways of counter-attacking this. But politicians think of controlling public opinion, and they are not so wise as to think beyond this immediate desire. We can see in certain political parties – I think the Labour Party in Britain is the same as the Social Democratic Party (SPD) here – that the generation that came out of the Second World War was more aware of these problems. They had suffered a lot through uniformity of opinion. But this generation has gone and now we have these professional politicians that are not able to really think in the common interest. To do that, it might require you to act against your own interest, to set free things that, privately, you might like to control. But that is then wisdom, something beyond just rational behaviour.

© Roland Reuß, 2015; © Robin Kinross, 2015