Our re-issue of two novels by E.C. Large, ‘Sugar in the air’ and ‘Asleep in the afternoon’, and publication of a companion work, ’God’s amateur’, prompted this piece in Lodown (no. 74), the magazine of ‘Populärkultur und Bewegungskunst’, published from Berlin. The introduction and email interviews are by Renko Heuer.

Looming Large

The modern movement has (rightly) been accused of political naïvety by supposing that optimized design was conceivable in mass production, where marketing arrangements will ensure a good product being swept away to stimulate fresh demand. Anyone who wishes to see such matters imaginatively explored should read E.C. Large’s novel ‘Sugar in the air’.

Norman Potter, What is a designer (4th edn., p. 39)

Sometimes the best stuff has been out there all along, waiting to be rediscovered and saved from obscurity. When Stuart Bailey (Dot Dot Dot; Dexter Sinister) and Robin Kinross of Hyphen Press, both of whom usually focus on design and typography, decided to release facsimile editions of E.C. Large’s novels Sugar in the air (originally published in 1937) and Asleep in the afternoon (1938), they rescued a long-forgotten literary treasure whose ‘peculiar charm’ is indeed ‘difficult to pinpoint’, as Stuart Bailey states below. It could be the understated precision of Large’s prose, his rather plain style, the modesty about it. It could be the intricate connection between the two novels, the latter being a metasequel to Sugar in the air that ‘continues, duplicates, and mirrors it all at once’, as Bailey writes in his essay ‘Science, fiction’ (which is included in God’s amateur, a companion to the works of Large, also released by Hyphen Press). It could also be the fact that these ‘scientific romances’ are not the kind of writing you’d expect from books published in the otherwise rather low-modernist (read: boring, unimaginative) 1930s, or how that strangely unassuming level of convolution doesn’t come off as mere playfulness. It could also be the protagonist himself, a man called Pry, who is – like Large, who was, successively, an industrial chemist, a writer, and a plant scientist ‘driven (not to say condemned) by a compulsion to identify local defects – “What exactly is going on here?” ’ While it’s probably all of the above, we have to say that E.C. Large certainly knew how to create a proper page-turner. You simply HAVE to read on. You want to know more about Pry’s fate, his respective projects’ fate, whether it is extracting sugar from the air or writing one of these novels (which, apart from sugar and novels, actually deal with a lot of things: the mass-market, design issues, love, sleep, bureaucratic absurdities) as if the paper was in fact sugar-coated.

Robin Kinross about discovering E.C. Large

Hyphen Press came into existence to make a new edition of Norman Potter’s book What is a designer, and it was Norman Potter who told me about these novels. Norman and I worked intensely together on his book, which was published at the end of 1980. I was under his spell, and picked up a lot of his enthusiasms and interests. I don’t know exactly when Norman first read the Large novels, but I imagine it was during the Second World War or soon after. Second-hand copies of Sugar in the air are quite easy to find in Britain: it was a small bestseller in its day and was reprinted soon after it was first published. By contrast, Asleep in the afternoon is hard to find: I think some of the stock may have been destroyed during the bombardment of London in 1940. When I came to try to buy a copy to scan for our reprint, I had to get one from the USA.

One of the formative episodes in Potter’s life was during the War. He got involved in a project to develop a machine to treat frostbite. All the people working on this were young dissidents of some kind; some were even actually ‘on the run’ and evading call-up into the armed forces. Norman himself was a very principled political anarchist and after the War he was given a prison sentence for having refused an identity card. This kind of rather British absurdity – anarchists being employed for state-funded scientific research – is very much the flavour of Sugar in the air. Sometimes I feel as if I am living in this novel, even now.

Sugar in the air appeals to young men (especially men, I think) who are trying to do something in the world. You have an idea, are trying to make it work, and find established interests set against you. I suppose Hyphen Press has some of this flavour, and I see the echoes of the novel also with friends who have invented devices and are trying to develop and sell them. I have never asked him, but I always assumed that this aspect of the novel was what appealed to Stuart Bailey.

I had always liked the two novels, after reading them first in the early 1980s. As Hyphen Press developed I would occasionally wonder about reprinting them. But it seemed crazy to publish fiction from within a list of books that is essentially about design. I knew Stuart first when he was a student in the early 1990s and we kept in touch. Stuart fell in love with these books and then urged me to re-publish them. Norman, me, and Stuart represent three generations – born roughly 25 years apart. So someone of an even younger generation had taken them up – and other young friends and colleagues did so too – and that gave me the impulse to start the project. It became a joint venture between Stuart and me, with permission and help from E.C. Large’s daughter, Jo Major. I had found her by writing to the British Mycological Society to ask for any contact details. Large was a plant scientist and was a leading figure in this organization.

Jo Major was of course pleased with the idea of reprinting the novels. The next step was to get permission from their first publisher, the firm of Jonathan Cape. This once very distinctive company is, of course, now part of a large conglomerate, Random House, which in turn is part of Bertelsmann AG. More echoes of Large’s world! I wrote an email asking permission to reissue the books. The reply said ‘yes, rights are available’ – with the implication, ‘and what will you offer for them?’. But by then the books had been out of print for at least 60 years. Anyone has the right to reissue them, as long as the author or his literary executor agree.

Stuart and I decided things very quickly: to republish both Sugar the air and its sequel Asleep in the afternoon together as a pair. As Stuart argues in his essay in our accompanying book, God’s amateur, they run together so much in their material that if you have read one you need to know the other. Treating them as facsimiles, scanning from the original pages, saved a lot of design decisions and it also lets the period flavour be visible in the pages of text. But we wanted to avoid any sense of pastiche or nostalgia and one way to do that was to publish them without loose jackets, either reproductions of the originals or our own attempt to make a cover design. We never thought about publishing them as one long book. We would have had to use ‘Bible paper’!

Will we publish more fiction?

I don’t think so. But I am glad that we have at least done these books. As well as wanting to bring these delightful novels back into circulation, I wanted to carry on with the idea that ‘design’ does not stop at visual style. In different ways all the Hyphen Press books have been about that. Sugar in the air, especially, throws light on the processes of business and finance; it also suggests something about the part that human personality can play in getting things done. Norman wrote in What is a designer that the success or failure of a job may seem to depend on the personality of one of the crucial people involved (a surveyor or a planning-department officer). All this is part of design too, and it’s something that Sugar in the air makes very clear.

What else are we doing?

Now I’m spending quite a large part of my energies on music CDs. These are recordings by the early music group The Bach Players. It was my initiative for them to start making CDs after more than 10 years of existence. They work as a collective and play without a conductor, and in this way have something in common with Hyphen Press. We’re putting some emphasis on the physical nature of these CDs, also the booklets that come with them are interesting and good value. This is the reason to get the CD and not just download the tracks.

I can see now that Morton Feldman says, a book of interviews with this American composer, was a first step into music. I wanted to do this book because I love the interview form, and Feldman was a really wonderful talker. You can love his conversation for its own sake, even without knowing his music. This project was suggested to me by Joseph Kohlmaier, an Austrian designer working in London, and he and I produced it, together with Chris Villars, the book’s editor. Now Joseph and I are working on another book: a translation of the book Mensch und Raum, by the philosopher Otto Friedrich Bollnow. This book has been continuously in print since its first edition of 1963, but is almost unknown in the English-speaking world. If one is thinking of building and architecture, then Bollnow’s book offers to open up perspectives: to let us understand the human, lived-in dimension of any structure or set of spaces.

What else? There are a few more projects to come in 2011 and thereafter. Looking further ahead, I think Hyphen Press will come to focus perhaps exclusively on the music CDs and on the small-format books that we can go on reprinting, including the book we started with, Norman Potter’s What is a designer.

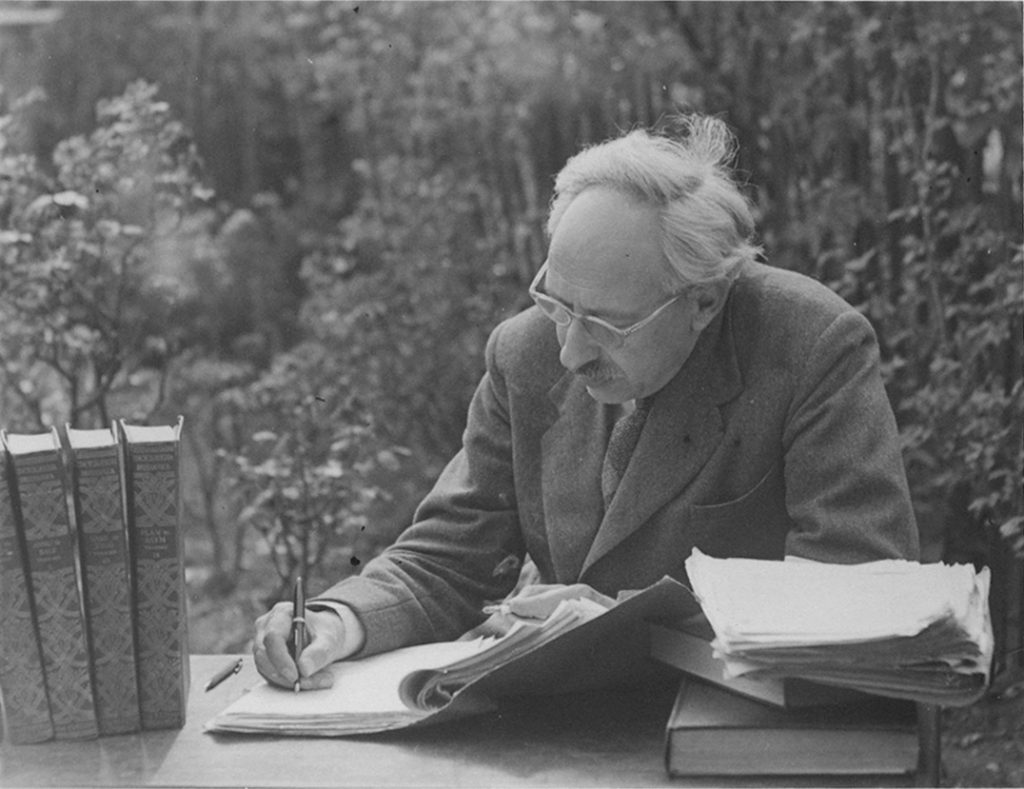

E.C. Large in 1956, at work on his last novel, Dawn in Andromeda, in the garden of his home.

Stuart Bailey on E.C. Large

Stuart, imagine ‘Sugar in the air’ without its sequel and the whole meta-layer: Would you still find it worthy of republication? Would you still say Large was ahead of his time?

Yes and no. I thought Sugar in the air was an extraordinary novel long before I read Asleep in the afternoon, and was probably already pressing Robin to republish it regardless. Its peculiar charm is difficult to pinpoint, but certainly has something to do with the protagonist’s wry, no-nonsense manner – you immediately sense that you’re in safe hands, that something will be explained or revealed – which is offset by a gentle, penetrating sarcasm that never quite tips over into irony. Although there’s no obvious meta-layer to Sugar in the air (while Asleep in the afternoon is defined by one, a book within a book), it’s already possible to sense something of Large’s detachment and self-awareness in the title, which is neatly designed to sound like a piece of throwaway whimsy while actually a straight-faced summary of its biochemical plot. And in a similarly subtle, double way, Pry’s characters are so patently stock ‘types’ that you begin to suspect that the clichés are deliberate, that Large is always a few steps ahead of his readers and up to something else altogether more intricate. This suspicion propels you through the book, and then right on into the next one. That’s how it worked for me, anyway. I couldn’t quite believe how Asleep took Sugar and simply squared the plot – a sequel about writing its prequel! But again, the wonder was peculiarly grounded, mundane even, and if anything makes the books unique, whether individually or as a pair, it’s this quotidian aspect. As such, it doesn’t seem right to describe Large as ‘ahead of his time’. In the essay ‘Science, fiction’ I tried to explain how I’d vaguely assumed this was the case until I actually thought properly about the historical lineage of metafiction – or at least the prehistory of what’s now commonly referred to as metafiction, from at least Sterne’s Tristram Shandy onwards. Now I’d describe the novels as ‘fresh’ rather than ‘vanguard’ – and the odd thing is that they still seem so, perhaps more now even than in the late 1930s.

Large was very much an amateur writer. What exactly is it that fascinates you about amateurs and dilettantes?

I wouldn’t say I’m fascinated by amateurs and dilettantes per se – I certainly prefer an expert to a hack. Brian Eno has a nice line about how the advantage a specifically ‘intelligent dilettante’ has over a ‘professional’ is that they are simply less likely to be limited by their own or others’ expectations; that they will tend to approach something on their own terms, from scratch, with a degree of useful innocence rather than on the basis of experience. This is not necessarily against things done well, or normally, or as usual, but it does usefully emphasize independence – thinking for yourself – rather than rote practice. This is certainly the sense in which it applies to Large and his alter ego Pry. Both are essentially self-policing, preferring to test and work things out for themselves, whether their experiments are scientific or fictional. The title of the third book of Large’s collected writings we published alongside the novels, God’s amateur, is drawn from Large’s own musings: ‘I shall begin “communicating” if I am not very careful. I spoke to an experienced friend of mine about this the other day and he said “God knows you for an amateur but Fleet Street will call you a pro”. I do not much care what Fleet Street calls me, so long as it helps the sale of my novels, but I rather hope that “God” will have no reason to change his mind.’