In a bravura act of publishing, Taschen Verlag has put out an extended selection, in facsimile, of the magazine ‘Domus’. This short review of the venture appears in the November issue of ‘Architecture Today’.

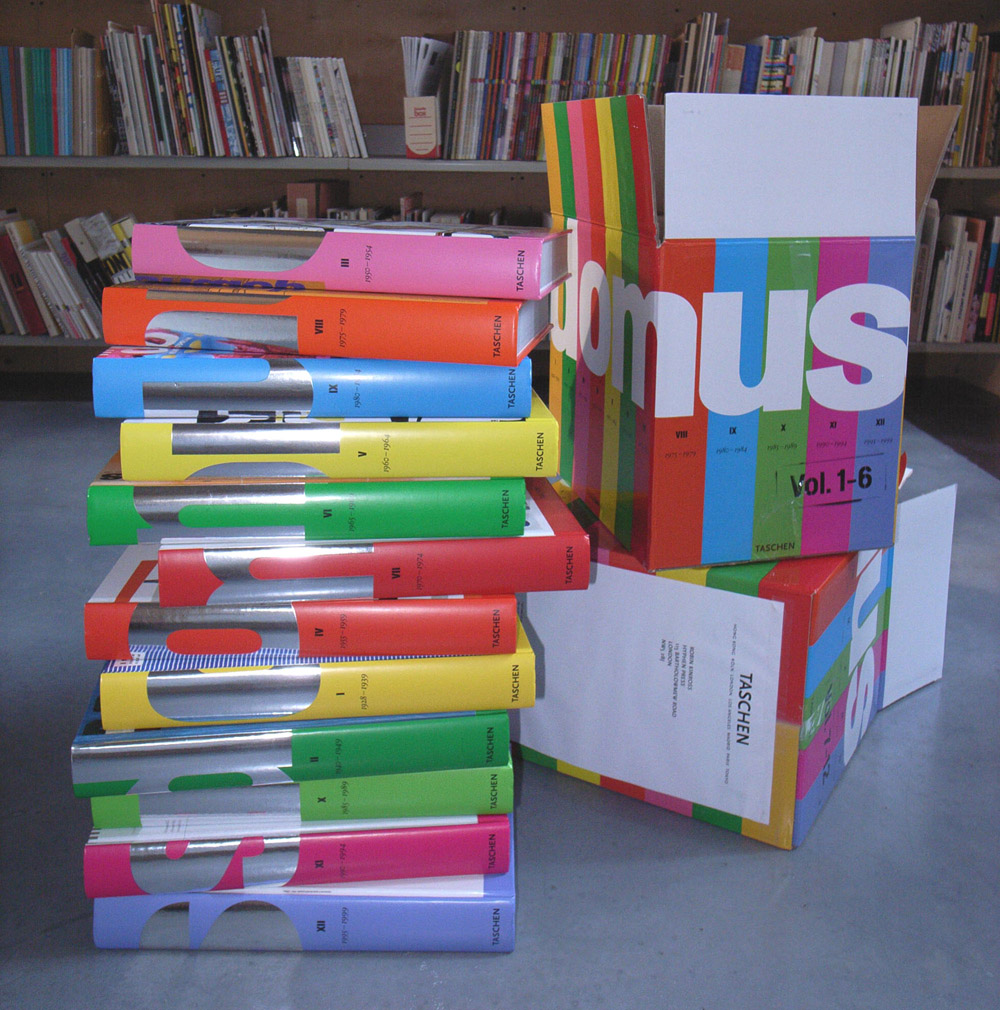

Domus 1928–1999, edited by Charlotte & Peter Fiell, published in 12 volumes by Taschen, £350

Domus has good claims to being the essential document of Italian design and architecture, embodying all the phases of its subject: emergence in the 1930s and the troubled deal with politics, glorious flourish in the postwar years, infamous over-styling in the 1980s, and the subsequent settling into the present internationalised global order of things. To reprint a selection from the magazine in facsimile was a brilliant notion – and one beset with difficulties that could hardly be solved. In their characteristic swaggering manner, Taschen have put the work into twelve heavy volumes, 2.75 kg each. They come in two wine-crate-sized boxes that will be anything but an impulse buy for the bookshop browser. One imagines that most of the sales will be via the internet, with Taschen offering free shipping for direct purchasers.

When the boxes arrive, prepare to lose a morning’s work as you leaf through the books, pausing to wonder at projects that you may know well, but which are here shown at their unveiling, in unfamiliar photographs. The facsimile reproduction faithfully captures the coarse half-tone screens, thickened black letterpress text, and queasy palette of the colour printing of the times. Follow Frank Gehry’s progress, month by month, from ingenious cheap builder to grand-budget formal inflater. Such progressions become vivid when followed in this way: one forgets temporarily what the end of the story will be, and it all becomes more understandable when read as a collective development, with several generations of designers grappling with the conditions of their time. In this way the back numbers of a magazine will always tell a truer story than any monograph, however fat, in which history is necessarily tidied up and given just one perspective. Even when the critical text is nervous and ambiguous, that too tells a truth. Thus Stanislaus von Moos on the Sainsbury Wing: ‘despite the troubling surprises offered by this design it may well result in the most beautiful and dignified recent museum yet to be seen on this side of the Atlantic.’ This is from the issue of June 1987, whose cover shows the GFT office building by Aldo Rossi, turned into graphics by the cover designer Italo Lupi. In such conjunctions and juxtapositions is history captured.

The disposition of the material seems to reflect the proportions of the original, with the first twenty years covered in the first two volumes, and subsequent volumes covering four or five year spans. The editors say they have chosen ‘the best of the best’ (most important and influential), with some element of personal taste creeping in. So the books constitute a useful archive, especially of Italian design in the 1940s and 1950s, which is still in the English-speaking world quite hard to discover. Each volume has an index of names, then gathered in a CD-Rom. While they were at it, the editors might have indexed the whole magazine, including all the pages they don’t reproduce. That really would be worth £350. Luigi Spinelli’s sharp summaries of the magazine’s history, spread over each volume, are very helpful. What is missing: the commentaries, the reviews, the discussions, all but the most ‘designed’ of the ads, in fact everything that makes Domus a magazine and not a book. Italian culture has been notable for the eloquence of its designers, sometimes all too ready to utter in print. It has also produced a few genuinely interesting designer-writers (Enrico Peressutti, Giancarlo de Carlo). Their words are entirely missing from this work. In its concentration on image, Taschen’s reprint offers a misleading view of Domus.

Robin Kinross