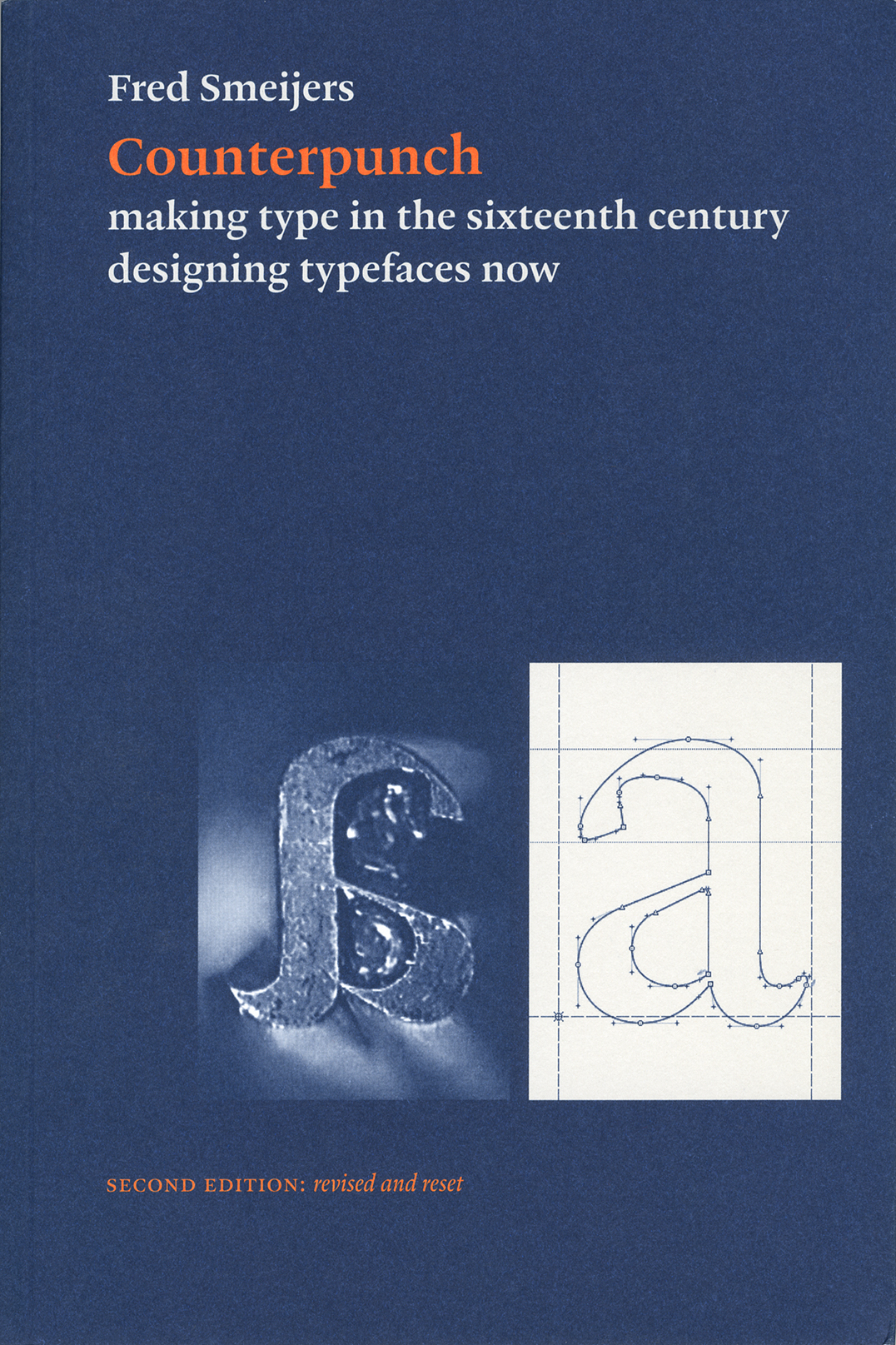

Counterpunch is packed with ideas. It is both an investigation into the technics of making metal type by hand, and a consideration of present questions in type design. The discussion takes in the fundamentals of designing and making letters, so that the book can be read as a guide to type and font construction in any medium. Lively, pointed drawings and photographs complement an equally fresh text.

Contents

Fundamental factors

Why this book?

Terminology

The three ways of making letters

Type: what it is and how it works

Comparing typefaces

Punchcutting in its contexts

Letters and the Italian intellect

The place of the punch in type production

The punchcutter and the historians

Where does the punchcutter come from?

The rise and fall of the punchcutter

Punchcutting in the sixteenth century

Punching and digging

The delights of steel

Fournier on punchcutting

How did they really do it?

Fixing the image

Sequence of design and production

One punch a day?

Where are the counterpunches

Hendrik van den Keere and outlines

Linearity

Punchcutting and the working of type

Does technique influence form?

The unconscious eye

To the future

Punchcutting in the digital age

Type design and language

The limits of roman

Openings and changes

Hendrik van den Keere

Renard

Illustration sources

Index

Synopsis

Typography is still dominated by letterforms from the first hundred years of European printing. What were the processes and attitudes that lie behind these forms? Fred Smeijers is a type designer who learnt to design and cut punches: the key instruments with which metal type is made. This book is a work of practical history, with much contemporary relevance.

Counterpunch opens with some basic questions: just what – in any age – is type? How does it differ from what we call writing? How to evaluate type? The historical discussion then begins with a look at the attitudes to letters of the Italian humanists in the fifteenth century. Their abstract ideals are contrasted with the material realities of production. These realities are also set against the idealism of historians.

Two approaches are distinguished: one that uses a set of counterpunches to make the punches, and one that engraves each punch freshly. Smeijers sees the counterpunch as an essential aid. It ensures regularity of form, repeatability, speed in production – in fact it gives a system of design, which will always be applicable to roman letterforms.

The central chapters of the book carry this argument forward, with a close look at the type and punches that survive from the sixteenth century, notably in the Plantin Museum at Antwerp. Here the illustrations are important: lucid line-drawings by Smeijers, photographs of early printing, and greatly enlarged photographs of punches – revealing them as the sculptures they are.

The book closes with some wider discussion, arguing for a way past the polarities of traditional/new-wave, and for clear socially-minded typography.

The second edition, like the first, is a high-quality flapped paperback, printed throughout in two colours. The text has been corrected and revised, and is reset in a new typeface (Haultin, designed by Smeijers).

Reviews

Smeijers, a Dutch type- and graphic designer, knows what he is talking about. Not an ivory-tower theoretician, he has practised punchcutting intensively. This shows, for example, in his commentary on two chapters of Pierre Simon Fournier’s ‘Manuel typographique’ of 1764, which Smeijers gives in an English translation and elucidates very instructively. The last part of the book extends the discussion to current type design and stresses the meaning of history for the present. Smeijers does not think that young designers nowadays must necessarily concern themselves with historical type, but he argues reasonably that they would profit from this.

‘Counterpunch’ is written in an entertaining manner and Smeijers’s ‘esprit’ frequently shines through – for which a compliment to the editor, Robin Kinross, is due. He revised the manuscript, largely written in English, without smoothing out the text too much. The carefully considered design, a bibliography, and a useful index complete a book that we can warmly recommend to anyone interested in type.

Kaspar Brand, Page [Hamburg], May 1997

It is no exaggeration that reading ‘Counterpunch’ is fun. … This book was not written for historians, ‘but for the makers and users of type,’ and anyone who has spent any amount of time intimate with the forms and counterforms of type will enjoy seeing the punchcutting experience through Smeijers’s eyes.

Angelynn Grant, Communication Arts, 1997

‘Counterpunch’ is a convincing argument, a strike back if you will, against the accepted theories of type design, history, and typography which have lead to a theory of mathematical precision in type forms that deadens their visual effect on the page.

Dan Carr, Matrix, 1997